Alcohol & Substance Use Disorders - Clinical Case Series #6

Adapted/Edited by Dr Gurjot Brar from "Evolution and Psychiatry: Clinical Cases" by Prof. Henry O'Connell

Welcome to the sixth in our clinical case series, exploring common mental disorders through the lens of evolutionary psychiatry. A ‘problem-based learning’ (PBL) approach is taken with learning outcomes defined at the outset, followed by several clinical encounters with fictional scenarios, interspersed with theory responding to the learning objectives. This method has emerged globally in medical curricula and has a good evidence base in medical education promoting self-directed learning. We hope you enjoy this format and look forward to your feedback.

This case series will often refer to key principles defined in the following article published in July 2023 which serves as a primer:

Evolution – basic principles & applications to health and illness

"Evolution and Psychiatry: Clinical Cases" is available hereThanks for reading Evolution and Psychiatry! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Alcohol & Substance Use Disorders

Learning Objectives

1. Outline the main clinical features, epidemiology, aetiological factors, assessment and treatment strategies of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and substance use disorders (SUDs),

2. List the main evolutionary theories relating to AUDs and SUDs.

3. Outline how evolutionary theories can be utilized in individual treatment strategies for AUDs and SUDs.

4. Outline how evolutionary theories can be utilized in wider public measures aimed at tackling AUDs and SUDs.

A Return Admission to St Aidan’s

Dr. Fogarty has been working as the senior Psychiatrist or Clinical Director for St. Aidan’s Addiction Treatment Centre for five years. This is a privately funded institution offering a mixture of inpatient/residential, outpatient and day services to people with alcohol and substance use disorders from all over Ireland. Dr. Fogarty is the clinical lead for a multidisciplinary team consisting of several mental health nurses and specifically trained addiction counsellors, a Social Worker, two Clinical Psychologists and an Occupational Therapist. Bed capacity at the centre is 50 and occupancy is usually near to 100%, with up to 50 more patients attending outpatient services daily.

Approximately one half of the patients attending St. Aidan’s have frequent relapses of their addiction problems and readmissions to the centre, the other half being new admissions. A key challenge for Dr. Fogarty and his colleagues is to reduce relapse rates and subsequent readmissions and increase the focus on treating patients with new onset problems.

One well known patient is Jenny O’Donovan, a 45 year old married mother of three children with a twenty year history of alcohol dependence syndrome. Dr. Fogarty remembers her as the first patient he admitted to St. Aidan’s five years before. Since then, Jenny has struggled with her addiction, usually having crisis admissions at least twice yearly. Along with her alcohol dependence, she has had three episodes of depression and she has had strong suicidal ideation during those episodes. She has multiple physical health problems relating to her drinking, including intermittently deranged hepatic function and a history of falls while intoxicated, once fracturing her forearm.

During the course of the past five years, Dr. Fogarty has got to know Jenny and her husband and children very well. They had a very successful business with a guesthouse and antique furniture shop in a scenic and touristy area in the west of Ireland. However, the costs of Jenny’s treatment and some unwise business decisions of hers over the past twenty years have pushed the business to the point of bankruptcy. Jenny’s husband Michael has always been very supportive and involved with her care, although Jenny sometimes blames him for the onset of her alcohol related problems because of an affair he had earlier in their relationship. The children have had their own problems, struggling with schoolwork and having frequent suspensions from school because of behavioural problems.

It is late on a Friday afternoon and Dr Fogarty is finishing paperwork before heading off for a brief and long anticipated holiday with his family. He has been examining the clinical activity data for St. Aidan’s and notes again with disappointment that return admissions continue to constitute at least half of their work. Dr Fogarty frequently reminds himself and his colleagues at St. Aidan’s that one of their key challenges is to reduce the readmission rate and focus more on brief interventions with new cohorts of patients.

As he is going over the clinical data and considering strategies to reduce the readmission rates, he receives a telephone call from the junior doctor on duty. ‘Sorry to bother you so late on a Friday, Dr Fogarty, but Jenny O’Donovan and her husband have just arrived. She wants readmission as she’s relapsed. She’s been drinking heavily for the past week and she’s in pretty bad shape’.

Dr Fogarty sighs audibly. He is thinking of the readmission statistics but, more importantly, he is disappointed for Jenny and her family. She had maintained sobriety for six months this time and he thought she was making progress. He had seen her in a recent outpatient group and she seemed very bright and positive.

As he walks to the admission office to meet Jenny and her husband he thinks of the nature of alcohol dependence and how the clinical criteria manifest so dramatically in badly affected individuals. When he arrives at the admission office he meets briefly with Jenny and her husband. They both look exhausted and upset. Jenny starts to cry: ‘I feel so ashamed to be back, Dr Fogarty. I only stopped drinking yesterday and I’m feeling a bit shaky now’. Then she forces a wry smile: ‘No offense, but I thought I would never have to come in to this place again’.

Dr Fogarty then has a brief discussion in private with the junior doctor where he outlines the clinical criteria for alcohol dependence syndrome

See Learning Objective 1: Regarding alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and substance use disorders (SUDs), outline the main clinical features, epidemiology, aetiological factors, assessment and treatment strategies.

The Murphy Sons

Having just finished up with the O’Donovan family, Dr Fogarty returns to his office and takes a brief moment to look out his window at the recreation space and garden below. Summer has started and the garden has returned to a haven of peace and tranquility.

Dr Fogarty is happy to see the patients enjoying the outdoor space. He feels like he knows them all very well at this stage, each with their individual stories of addiction battles and shattered lives.

Along with the O’Donovans, Dr Fogarty has also got to know countless other families very well over the past five years, the Murphys being one. All three of the now adult sons have had significant problems with illicit drug use over several years and all have availed of the services at St. Aidan’s at different stages.

The Murphy parents are both medical doctors and have spent the past decade trying to help get their sons sober from drugs. The two younger sons are now in prison for drug dealing offences. Those two sons have used mainly marijuana, cocaine and amphetamines down through the years. They are bright young men and both came close to finishing college degrees but ultimately had to drop out because of their drug use.

Dr Fogarty has a special fondness for the eldest Murphy son, Mark. He remembers when he first met with Mark five years ago. Mark was shy and self-conscious and had decided that the only way he could ever talk to women was by being stoned. Then he could sing and play his guitar and feel at ease with himself. But his marijuana use had escalated and he had gone on to using cocaine also as a social crutch. Now in his mid-thirties, Mark had moved to injecting heroin in the past year. He has been involved in petty crime to fund his heroin use but he has always managed to avoid jail. Mark is very warm and friendly and, during his brief periods of sobriety, he speaks eloquently in therapy groups about the power of addiction on him and his brothers and on how they have ‘no excuses’ for their drug use, considering that they were raised in a stable and loving home.

Like Jenny O’Donovan, Mark Murphy has recently been readmitted due to increasingly chaotic drug use. The plan now is that he may start opiate replacement therapy such as Methadone.

Dr Fogarty watches Mark walking slow circuits of the garden alone. He recognizes his tall frame and sloping stride, but he sees that Mark has become very gaunt, with cheeks sucked in due to loss of so many of his teeth. Although always friendly whenever they meet, seen from a distance Mark looks like someone who is lost in his own personal hell, staring ahead vacantly as he slowly walks lap after lap of the garden.

Dr Fogarty reflects on the clinical criteria for substance use disorders generally and how similar the criteria for alcohol use disorders is (AUDs). The Murphy sons and Jenny Donovan are such tragic examples of the power and carnage wrought by addiction.

See Learning Objective 1: Regarding alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and substance use disorders (SUDs), outline the main clinical features, epidemiology, aetiological factors, assessment and treatment strategies.

Learning Objective 1: Regarding alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and substance use disorders (SUDs), outline the main clinical features, epidemiology, aetiological factors, assessment and treatment strategies.

Alcohol and substance use disorders are associated with untold damage and human suffering worldwide. Globally, more than 280 million people aged 15-64 use drugs and/or alcohol, a 26 percent increase over the previous decade. The most frequently used substances include alcohol and nicotine followed by cannabis, amphetamines and ecstasy and then opiates and cocaine (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022). The clinical diagnostic criteria for alcohol and substance dependence include evidence of tolerance to the effects of the substance (with increasing amounts consumed over time), a persistent desire and craving for the substance, loss of control over substance use, a physiological withdrawal state on cessation of use, continued use of the substance despite evidence of harmful effects and the neglect of social and occupational commitments.

Substance abuse represents a major public health issue wreaking havoc on socioeconomic structures, and contributes to crime, mental disorder, and medical issues (Roberts et al., 2014). Psychological and psychiatric aspects of misuse include problems related to antisocial behaviour, depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), and diminished abilities to modulate emotions and behaviours in stressful contexts (Haug et al., 2014). Almost half of patients attending community mental health teams (CMHTs) report drug use and/or harmful alcohol use in the past year and 75-85% of patients attending drug and alcohol services had a psychiatric disorder in the last year (Weaver et al., 2003). Drug use and mental disorders are frequently co-morbid, with bi-directional cause and effect but initiation is at least partially explained by self-medication and/or symptom alleviation (Khantzian, 2003).

Local cultural and societal factors are important. For example, in countries and cultures where alcohol use is prohibited, alcohol use disorders are much less prevalent. The specific psychological and behavioural impacts of various substances also vary widely.

Aetiology is complex and is related to cultural factors, genetics and early life experiences. Assessment and treatment should be based on a non-judgmental approach that takes into account multiple sources and engages patients in a comprehensive biopsychosocial treatment plan. Again, assessment and treatment strategies will vary widely depending on the substance or substances in question and the clinical and sociodemographic profile of the patient.

The St. Aidan’s Day Lecture

Dr. Fogarty is preparing to give his annual St. Aidan’s Day lecture for staff, patients and their families. Also in attendance will be some local politicians and financial benefactors. For this lecture, he generally reviews the clinical data of the service for the year just gone and sets out a service plan for the year ahead. For the second part of the lecture he then outlines some key recent scientific developments in addiction treatment, such as potential breakthrough medications or new forms of psychotherapy. This will be Dr Fogarty’s sixth such lecture as the Clinical Director for St. Aidan’s.

For his lecture, Dr Fogarty wants to acknowledge the great work and many success stories of the hospital service, but he is also aware of those patients and families who have had to return again and again in crisis and seem to make little progress. Among the hundreds in the audience will be many patients and families well known to him, such as the O’Donovans and the Murphys. As some local politicians and potential benefactors will also be present, and Dr Fogarty hopes that his lecture will attract new funding and resources for St. Aidan’s.

Dr Fogarty has been reviewing the clinical scientific literature in recent weeks and sees little in terms of new ground-breaking research for inclusion in his lecture. However, a further trawl in the literature opens up to him the potential for applying evolutionary principles to the study of addictions. Reading this material gives Dr Fogarty a renewed sense of optimism and he is now looking forward to presenting to the St. Aidan’s community some fresh perspectives for the year ahead. He decides to base his lecture around evolutionary principles and present evidence for and against the main theories. He reviews the most recent evidence in the area and finds that there are ten areas of potential relevance from the evolutionary perspective.

Learning Objective 2: Outline the main evolutionary theories relating to AUDs and SUDs.

St. John-Smith & Abed (2022) have recently reviewed and summarized the main evolutionary perspectives on alcohol and substance use disorders, as listed below and grouped under four main sections. We will focus in detail on the more popular theories below.

In general terms, psychoactive substances may be used to palliate negative affect and pain (e.g. opioids) and/or to increase positive affect (e.g. stimulants). The evolutionary perspectives allows us to ask and potentially answer several important questions such as (Abed & St John-Smith, 2022):

a) Why do plants produce substances that alter the nervous systems of humans?

b) Why are some neurotoxin substances addictive to humans?

c) Why do humans continue to seek and consume non-nutritional substances and become dependent on them?

Mismatch-based Models

Generic mismatch

Hijack Model

Novel Psychoactive Substances

Trade-off-based Models

Pharmacophagy

Neurotoxin-regulation

Models Based on Selection for Risk-taking Behaviour and Signaling

Sexual Selection

Costly Signaling

Life History-based Models

Others

Foetal Protection Hypothesis

Shamanic Model of Psychedelic Drug Use

Mismatch-based Models are based on one of Nesse’s key evolutionary principles (Nesse, 2022), whereby some mental disorders are seen to arise as a result of a mismatch between evolved traits and our modern and increasingly unnatural environmental circumstances and challenges.

For example, while an attraction to the low levels of alcohol released by ripe fruit (e.g. 4% ABV) may have been evolutionarily adaptive in our hunter-gatherer past, in helping with olfactory localization of valuable nutritional resources). It is believed that humans inherited the pair of enzymes (alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase) involved in converting alcohol around 10 million years from African apes (Carrigan, 2020). The exploitation of fermented fruits from the forest floor likely continued to be a major source of high-energy foods up until the genus Homo appeared around 2 million years ago (Dunbar, 2022a) Unfortunately the high concentration and ubiquitous availability of modern alcoholic beverages (in some cultures at least) can lead to untold personal and societal harm.

Furthermore, the ‘hijack’ theory proposes that modern high alcohol concentration beverages and novel psychoactive substances such as synthetic drugs may ‘hijack’ the mesolimbic reward pathway, thus forming the neurochemical basis for addictive behaviours. According to this model, drugs of abuse have a unique ability to ‘hijack’ the ancient and evolutionarily conserved neural mechanisms in the brain that are associated with positive emotions. These mechanisms evolved over time to incentivize adaptive behaviour, a crucial aspect of human fitness. The mesolimbic dopamine system (MDS) is implicated here to play a key role in Pavlovian condition and other forms of reinforcement learning. Research has demonstrated that although drugs of abuse differ in molecular structures and substrates, they converge on this common pathway where dopamine is frequently implicated. Furthermore, the MDS appears to have evolved to provide reinforcement for natural rewards and behaviours which historically increased fitness (mates, allies, food etc.) (Sullivan et al., 2008).

Novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) provide a classic example of mismatch. Chemists can synthesise drug molecules that have never been encountered by humans during their evolutionary history and thus have never evolved defences against them. Psychostimulants such as modafinil and synthetic cocaine substitutes produce false perceptions of fitness and improvement of competitive strategies while sedatives and anxiolytics (benzodiazepines and synthetic opioids) produce euphoria and disinhibition, perceived increased control of fear and enhanced control of painful stimuli (Schifano et al., 2015). As these effects are detached from their evolved, adaptive contexts there are growing concerns how our bodies will manage to defend, detoxify and deal with the unintended harmful effects of such NPSs (Orsolini et al., 2017)

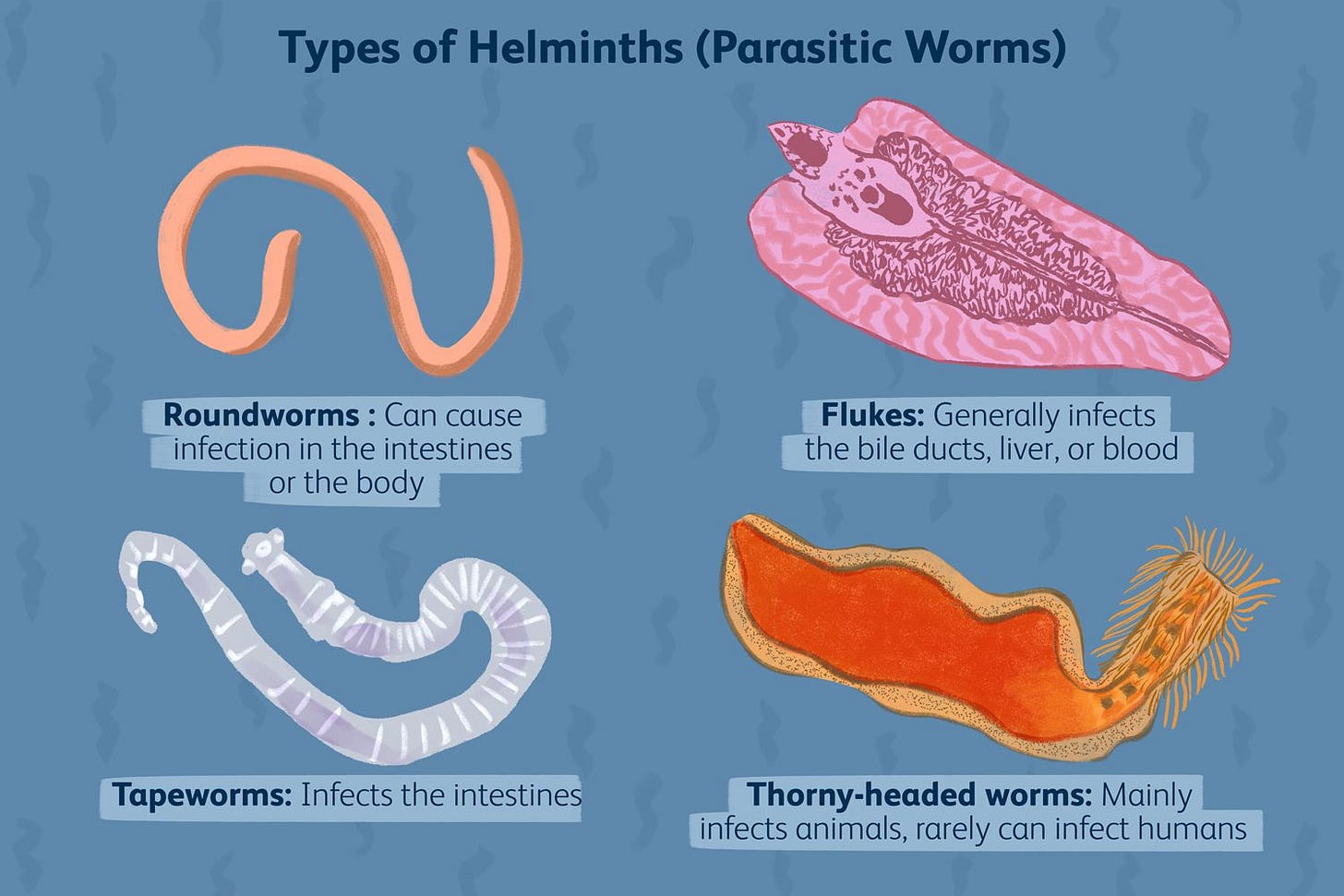

The pharmacophagy hypothesis proposes that in a long process of co-evolution between plants and animals including humans the neurotoxins produced by plants to deter consumption by animals may have, in small doses at least, health benefits for those animals that can consume them (Hagen et al., 2013), Along with the nutritional benefits of plant consumption, consumption of plant alkaloids may have antimicrobial effects and a taste for such plant chemicals may have been selected for. For example, nicotine is both insecticidal and anti-helminthic, and is associated with reduced helminthic infestation in hunter-gatherer studies (Roulette et al., 2014; Roulette et al., 2016).

The models based on selection for risk-taking behaviour and sexual signaling are more complex. Fast life history strategies (Nettle & Frankenhuis, 2020) may include chaotic use of alcohol and drugs as a symptom reflecting an overall pattern of impulsive behaviour and emotional dysregulation. Consumption of alcohol or drugs may also facilitate communication, social interaction with the opposite gender and ‘honest’ signaling of biological health, thus enhancing sexual selection. The male preponderance and greater vulnerability of young adults/adolescents to develop alcohol and substance use problems than other age groups can be partly explained by life history theory. Additionally, those unmarried and with a lower socioeconomic status (who may benefit from high risk-taking strategies), have a higher prevalence of substance use disorders (Reyna & Farley, 2006; St John-Smith & Abed, 2022; St John-Smith et al., 2013)

A more tenuous theory relates to the use of psychoactive substances, especially psychedelics, in facilitating shamanic practices and religious and mystical rituals via group cohesion and bonding (Polimeni, 2012; Dunbar, 2022b).

Questions and answers

Dr Fogarty’s lecture is well received and there follows a lively questions and answers session with the audience. Everyone seems to be fascinated with these evolutionary perspectives and many patients, both current and past, give powerful testimonies of how these theories make sense to them personally.

A former patient of the hospital who has now been sober for several years stands up and bravely recalls his experiences with alcohol and drug addiction when he was in his twenties and thirties. ‘This evolutionary perspective makes so much sense to me. I really did feel that my brain had been hijacked by alcohol and drugs. I had lost control and could do nothing, even though I knew that I was destroying everything around me. I know it doesn’t excuse my behaviour but I know now that it was more than just me making bad decisions or being flawed in some way as a person’.

Others join in with similar reflections. Dr Fogarty is conscious too of those who are still struggling and are in active treatment with the service. Not everyone here has a success story to share. He is about to make this point when Jenny O’Donovan stands up and smiles nervously. ‘Thank you Dr Fogarty. I know how hard you and the St. Aidan’s team work. But I still keep coming back, again and again. No offense, but I really don’t want to be here. And while your talk tonight was very interesting, I’m struggling to see how these evolutionary perspectives can help me’.

Learning Objective 3: Outline how evolutionary theories can be utilized in individual treatment strategies for AUDs and SUDs.

As with other mental disorders, the evolutionary perspective introduces ultimate as well as proximate explanations for our risk as a species for developing alcohol and substance use disorders. These explanations are outlined in the earlier learning objective and include explanations related to palliation or enhancement of negative and positive affective states respectively, environmental mismatch, evolutionary trade-offs, sexual selection and other miscellaneous areas.

Knowledge of these broad evolutionary perspectives is likely to destigmatize and help encourage non-judgmental approaches to conceptualizing alcohol and substance use disorders. Therefore, individual sufferers, family members and healthcare workers can be encouraged by the evolutionary perspective to think of alcohol and substance use disorders as universal problems for which we are all at risk, as opposed to more traditional perspectives that have sometimes implied characterological flaws or poor decision making as the primary drivers.

This move towards more non-judgmental perspectives is likely to be the single biggest contribution of evolutionary perspectives to the study and treatment of alcohol and substance use disorders. This primary insight is that we are all vulnerable to the allure of novel psychoactive substances which ‘hi-jack’ our evolved motivational-emotional systems designed to reward and thus promote the pursuit of natural rewards in ancestral environments. The environmental mismatch found in contemporary environments with vastly larger quantities and more potent substances yields problematic levels and patterns of use.

Individual and group psychotherapy approaches can be further enhanced by acknowledging the potency of modern alcohol and drugs in comparison to the much milder, naturally occurring psychoactive substances in our phylogenetic history. The potential for ‘hijacking’ of innate reward systems by alcohol and drugs, thus leading to a whole syndrome of addiction related symptoms and behaviours, can also be used in psychoeducation and psychotherapy.

And just as alcohol and other psychoactive substances may ‘hijack’ the mesolimbic reward system, individual psychotherapy and rehabilitation treatment plans may benefit from focussing on alternative, healthier and more adaptive ‘hijacking’ activities and behaviours, such as exercise and other goal orientated pursuits that can tap into and activate innate reward systems.

Individual and group therapy should also obviously focus on identifying and treating underlying affective and psychotic comorbid psychiatric disorders that patients may have been self-medicating with alcohol or drugs. A classic example here is the socially phobic young man who needs the ‘Dutch courage’ of alcohol to help him talk to women and who ultimately develops alcohol related problems because of his overreliance on alcohol as a social crutch.

The insights evolutionary psychiatry brings are compatible with mainstream biopsychosocial formulation and treatment. Reducing physical harm caused by drug use, treating co-morbidities and targeting the mesocorticolimbic reward pathway with pharmacological agents represent biological pathways suitable for modification. Psychologically, treatment could be aimed at, enhancing self-regulatory capacities, psychoeducation, increasing response inhibition, weakening cued associations, and readily acknowledging negative consequences of use. The social domain is also a good area for preventing and treating substance use disorders. Improving the environment and socioeconomic status of impoverished or marginalised youth may reduce the propensity for risk-taking and fast-life strategies. Furthermore, recognising that adolescence represents a vulnerable period for the development of substance use issues, families and communities should be encouraged to act as ‘surrogate frontal lobes’ to attenuate risk-taking tendencies (Durrant et al., 2009). Natural rewards or ‘primary goods’ (Ward & Stewart, 2003) gained through friendship and community may contribute to prevention and treatment which reduce the likelihood of false rewards gained from drugs and also highlight and amplify the perceived costs of addictive behaviour. Understanding the role of life events and experiences of an individual may allow deeper appreciation of their individual risk of addiction and relapse and aid in tailoring treatment (Klingemann & Sobell, 2007). Put together, a tripartite model aimed at the biological, psychological, and social levels, buttressed by an evolutionary informed approach, is likely to be more effective than purely achieving abstinence.

“As an expert in this area, I wonder if you would have any policy recommendations for the Minister?”

The lecture session is coming to an end, and Dr Fogarty’s outline of evolutionary perspectives on addiction has generated a lot of discussion among the patients and their families. Some of his clinical colleagues have started to make proposals for how the treatment programmes can be improved by incorporating evolutionary perspectives.

With just a few minutes left, local politician Michael Morrissey stands up. ‘Wonderful work you do here, Dr Fogarty, and a wonderful talk tonight. I will be very happy to go back to the local council and also contact my colleagues in government to see if we can increase the state funding available to St. Aidan’s’. Dr Fogarty thanks Mr. Morrissey for his comments and support, aware that private fees alone are never enough to keep St. Aidan’s functioning and that government support is also needed.

Mr. Morrissey then goes on: ‘I will also meeting the Minister for Health in Dublin next week. We will be discussing issues relating to healthcare strategy in this region and also some national policies and objectives. As an expert in this area, I wonder Dr Fogarty if you would have any policy recommendations for the Minister, informed by this evolutionary perspective, that could help diminish the burden of alcohol and drug use problems on our population?’

Learning Objective 4: Outline how evolutionary theories can be utilized in wider public measures aimed at tackling AUDs and SUDs.

As outlined in the earlier learning objective, a crucial contribution of the evolutionary perspective should be the introduction of a non-judgmental approach to the conceptualization and treatment of alcohol and substance use disorders. This approach recognises that all humans, given a particular set of circumstances, will be vulnerable to substance abuse and addiction

The potency of alcohol and drugs in hijacking innate reward systems should be highlighted in public awareness and education campaigns, especially those aimed at younger people who are at heightened risk of alcohol and drug related for a whole range of reasons, including neurocognitive immaturity.

Using an evolutionary perspective, policymakers can be encouraged to invest in public health measures which seek to prevent and reduce addiction issues at the outset, rather than relying on purely punitive penal measures and sanctions. Furthermore, following the successful work of Babor et al., (2003) in demonstrating harm limitation with alcohol and maximizing the chances for negative consequences for drink-driving, similar approaches of demand reduction and supply limitation can be utilised through measures such as taxation and restrictions of sale and supply to reduce problematic behaviour in other substances (Ghodse, 2003). However this is recognised to be politically controversial and difficult to implement fully.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast

Great article. Evolution should always be looked at to allow for explanations for human behavior. It makes sense and allows for more compassion for those who suffer addiction problems.

I’d put these patients on a carnivore diet! Is so it ASAP. Especially the alcoholics.

We cured my husband of alcoholism on the carnivore diet. He was a life long drinker and would quit for no body. I had resigned my self to him drinking until he either died or ended up in a nursing home. Carnivore diet cured him. There is a sugar alcohol connection. I’m a sugar addict and my husband was a alcoholic. Carnivore cured both.