Attachment Theory and Evolutionary Psychiatry

Written by Dr Gerry Rafferty - Edited by Dr Gurjot Brar and Prof. Henry O'Connell

Dr Gerry Rafferty provides a personal and professional reflection on Attachment Theory and its relevance to Evolutionary Psychiatry.

Evolutionary psychiatry and attachment theory share a conceptual link in their understanding of the development and functioning of the human mind and behaviour. While distinct fields of study, they both provide valuable insights into understanding mental health and behaviour from different perspectives. It has been proposed that attachment theory is a secondary mediator of the evolutionary progress.

Evolutionary psychiatry focuses on the evolutionary origins and adaptive functions of psychiatric symptoms and behaviours. For example, it explores how natural selection shaped our psychological mechanisms and how certain traits and behaviours that were once advantageous may now contribute to mental health problems in modern environments. Evolutionary psychiatry seeks to explain how we remain vulnerable to mental disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and addiction, as a result of maladaptive responses to evolutionary challenges.

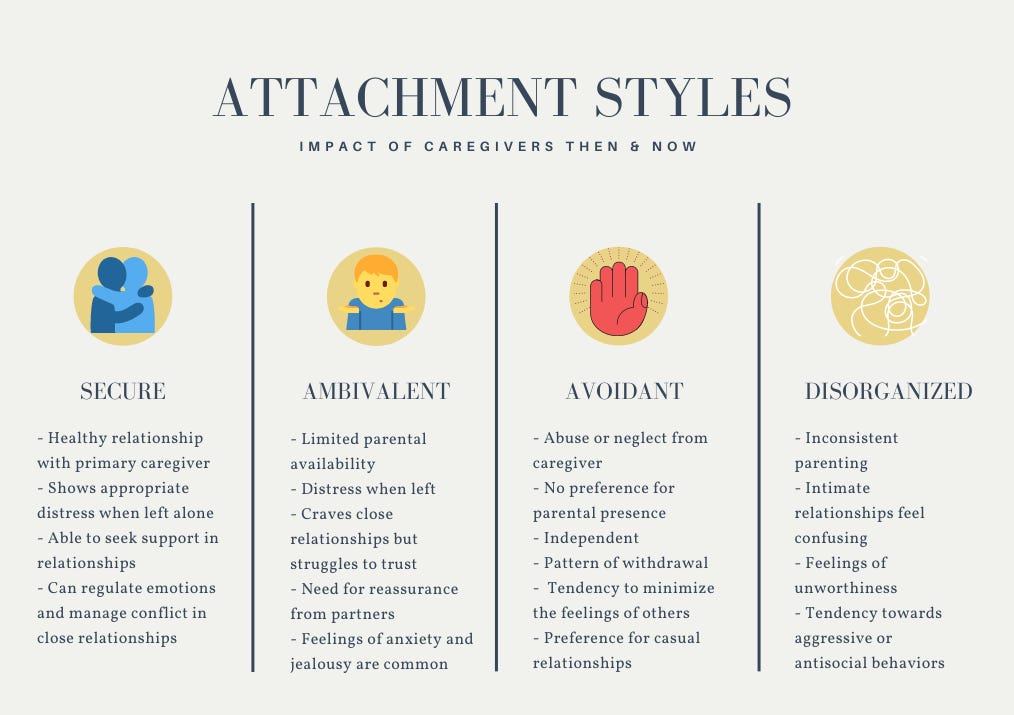

Attachment theory, on the other hand, was initially proposed by John Bowlby who interestingly was a biographer of Darwin. It examines the emotional bond between individuals, particularly the attachment bond between infants and their primary caregivers. Attachment theory suggests that early experiences with caregivers shape an individual's internal working model, influencing their social and emotional development throughout life. It describes different attachment styles, such as secure, anxious-ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganised, and their impact on relationships and psychological well-being. Bowlby would have had a very reductionist view of the role of attachment in evolution as simply the protection of progeny. Ainsworth would have disagreed and added training of the young. In doing so she opened the way to viewing ontogeny and phylogeny play interdependent and crucial roles in development of a species (Granqvist, 2021)

The link between evolutionary psychiatry and attachment theory lies in their shared interest in understanding human behaviour and mental health in the context of evolutionary processes. Attachment theory emphasises the importance of early social experiences and the need for secure attachment bonds, which provide a foundation for healthy emotional and interpersonal functioning. Evolutionary psychiatry seeks to explain how natural selection has influenced the development of these attachment behaviours and how disruptions or mismatches between evolved mechanisms and modern environments can potentially lead to psychiatric disorders.

In this sense, evolutionary psychiatry can offer insights into the adaptive value of attachment behaviours and how they may have contributed to survival and reproductive success in our ancestral past. It can help explain why certain attachment styles may be more prevalent in diverse populations and shed light on the origins of psychological vulnerabilities or predispositions to mental health disorders (Platts et al., 2002).

Overall, while evolutionary psychiatry and attachment theory are enmeshed fields fields, they share common ground in their attempts to understand the complex interplay between biology, environment, and psychology in shaping human behaviour and mental health. It has been argued that attachment theory is the only hypothesis which has an evolutionary basis (Cassidy & Shaver, 2002). However the distinction may overlook some evolutionary facts.

I breed horses in my other life, and this is the time of the year when the foals are out in the fields with their mothers. Attachment theory occurring in vivo. Foals begin to learn to gallop and run in concentric circles from their secure base. If this attachment is broken during birth or in very early infancy, the foals can become untrainable and prone to suffer injuries. Taking an evolutionary perspective, higher mammals give birth to young that are incapable of independent existence for increasing long periods of infancy. During this extended “childhood” a large amount of neurological development continues ex utero and is mediated on the attachment relationship between infant and primary care caregiver. What is also evident as you progress along the brain volume of mammals is that the consequences of attachment are bidirectional. Mares who have previously lost foals in infancy behave very differently in subsequent pregnancies. Previously, they engage in checking behaviour and are reluctant to be on their own, often requiring companions for the duration of the pregnancy. We tend to have as many donkeys as breeding mares as they appear to have a calming effect. Same is true of human mothers, in a serendipitous life history I was an obstetrician for 20 years dealing with high risk pregnancies. There are far more similarities than differences in how the two groups behave. There is an obvious common process at work when you sit in a field and watch the mares teach their foals to run bit by bit further away to when you are sitting on a bench in the park on a Saturday when you have taken your children to the playground. The same process of safe exploration from a secure base can be seen in children learning to ride a bike and foals learning to gallop. Every mother soon recognises the expression of mixed anxiety and pride , a commonality to both sets of parents. This would therefore suggest that there is a link between more complex neurological development, relative immaturity at birth and the attachment model of caregiver and child as an important evolutionary step.

Humans and their ancestors took this step significantly forward when we stood up. The increased human brain size and reduced birth canal size consequent on being bipedal meant we gave birth to neurologically very immature offspring, leaving a significant amount of neurological and cognitive development to continue ex utero. What Bowlby and Ainsworth demonstrated is that emotional and relationship development occurred in the first eighteen months of life. The described effects of stimulus and attachment models having profound effects on lifelong behaviour and development. The importance of the first 1000 days of life are now well recognised as major contributions of life long mental and physical health (Indrio et al., 2022).

There has been a view taken that attachment disorder (or fracture) is a sociological or behavioural disturbance. The bio-psycho-social model supports this approach. This consequentially informs interventions in terms of mainly sociological terms, leading to crucial omissions in understanding this complex interaction. Viewing attachment theory as a mediator of an evolutionary process that allows for complex neurological development may be a more functionally relevant perspective.

Where evolution and attachment tend to agree is that nurture and stimulus enhances development. The psychodynamic informed attachment theory would place this responsibility on the parent, however evolutionary psychiatry may disperse it amongst the pack or tribe. This is by no means a new point of view, a traditional Irish saying would state that it takes “ a village to raise a child”. This view may be more in keeping with evolutionary principles, such as the benefits of allo-parenting in hunter gather population. This view would also be in keeping with the “grandmother hypothesis”, that extended kin lifespan following menopause may play a role in enhancing the development of the infant (Perry & Daly, 2017). Both attachment and evolutionary theory might suggest that the “nuclear family” is a flawed 20th century concept which may have promoted industrialisation and urban development. As the challenge to house and accommodate the world’s population deepens, perhaps we would do well to consider a return to fundamental principles.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast