Evolving Psychiatry & Adam Hunt

In this article I speak to Adam Hunt who is a PhD student at the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich and the host of the Evolving Psychiatry podcast.

Hi Adam, thank you for taking the time to speak with me perhaps we could begin by you introducing yourself for those who don’t know you?

I’m Adam Hunt, currently finishing up my PhD at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, in the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine. My research is focused on evolutionary psychiatry, specifically looking at improving methods and conceptual frameworks, with particular concentration on theory explaining individual differences and relating that to psychiatric conditions. I’m also intertwined with the global evolutionary psychiatry community and try and help out there as much as I can – in particular, I run the UK RCPsych evolutionary psychiatry group’s YouTube, the WPA group’s webinars, host the ‘Evolving Psychiatry’ podcast and all sorts of other things. You can check out short blog posts on most of these activities on my website.

It seems you’re one of the few that is doing a PhD in evolutionary psychiatry, how were you introduced to the field?

I actually stumbled upon the core paradox of evolutionary psychiatry before really knowing it was a field.

Like many, I had always assumed mental disorders were diseases like any other – problems or breakages not needing explanation beyond ‘something has gone wrong with this person’s brain’.

That changed on the night of the 3rd of June 2016 (I remember it vividly). Whilst randomly doing some research into schizophrenia, I realized a paradox exists, of ‘common, harmful, heritable mental disorders’ – which is the phrase coined by Keller and Miller (they actually missed out ‘early-onset’, an additional necessary component for the paradox; late-onset diseases aren’t a paradox as they can be ‘invisible’ to natural selection). This has actually been recognized since the mid twentieth century as ‘the schizophrenia paradox’.

The paradox is simple: if these conditions are truly heritable diseases, they should have been removed from the population by natural selection – but they are extremely common – schizophrenia, autism, ADHD, psychopathy, bipolar, and so on, each exist in around or over 1% of the population. In fact, at these levels, every one of our hunter-gatherer ancestors (who regularly socialized with and personally knew at least 150 people) should have lived with someone who would classify with every major mental disorder. Decades of research had failed to find underlying pathology behind any of these conditions, despite billions of dollars spent and tens of thousands of scientists studying them from looking for traditional diseases. The evolutionary perspective seemed like it had to hold the key.

At the point of realizing this, I had received my Masters in philosophy from the University of Bristol, where I had studied the philosophy of biology and philosophy of psychology; in particular, I had a good grounding in evolutionary theory from my philosophy of biology courses. And I am very interested in understanding the world and thinking about big problems which affect humanity! So I basically became obsessed with trying to apply evolutionary theory to explain mental disorders, feeling that there must be something there, and that it was a radically important perspective entirely missing from public discourse. At the time in 2016, there were basically no available mainstream books on evolutionary psychiatry, very little information available online, and it seemed like nobody was really doing the work which I thought needed to be done, so I decided to do it myself. I looked for PhD programs but none existed, so I left my job to do research and write a book.

The paradox is simple: if these conditions are truly heritable diseases, they should have been removed from the population by natural selection – but they are extremely common – schizophrenia, autism, ADHD, psychopathy, bipolar, and so on, each exist in around or over 1% of the population. In fact, at these levels, every one of our hunter-gatherer ancestors (who regularly socialized with and personally knew at least 150 people) should have lived with someone who would classify with every major mental disorder.

I thought it might take six months... Four years later, I was up to speed on the important research and had a decent book draft in hand, at which time I looked again for PhD programs. Luckily I stumbled upon this recently established department in Zurich, the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine, and found my supervisor, Adrian Jaeggi, an evolutionary anthropologist who has diverse interests and was willing to take me on as a PhD once he had read the book draft. I also came across the UK Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group, which hadn’t existed in 2016 when I was first looking (they actually set up that very year) and got involved with them. I found some funding in Zurich to allow me to stay here for a few years and properly convert my work into my PhD. I’m just finishing up now!

Can you quickly take us through some of your published academic work? What is the evobiopsychosocial model? What are ‘specialised minds’? How do you think these improve on the current paradigm?

The evobiopsychosocial model is something I developed with Riadh Abed and Paul St-John Smith after reading Bolton and Gillet’s recent attempted update of the biopsychosocial model and finding it contained no reference to evolutionary theory! As avid evolutionists we thought this was a huge oversight – clearly any complete understanding of health will have to reference evolution in some way. The evobiopsychosocial is a conceptual framework pointing out that the biological, psychological and social all need to be made sense of from an evolutionary perspective, and we can gain both theoretical and practical benefits from doing so, as well as forming a more scientifically sound model. It’s published in an open access paper here, and introduced at more length in an introductory chapter to the Evolutionary Psychiatry CUP book.

For example, we can think about biological, psychological and social causes of depression, but without the evolutionary depth of analysis we don’t fully understand what’s going on, and might miss some critical insights. On the biological level, the fact that human brains are so different to rat or mice brains means testing antidepressants on rats and mice is pretty inappropriate – we should be looking for animals who have more similar brains and, ideally, social circumstances to us. The degree to which an animal model is phylogenetically conserved is the precise degree to which that animal model is useful for drug testing – this is overlooked by biomedicine in the interests of cost and tradition, but is a critical problem with developing and testing psychiatric drugs. On psychosocial levels, if depression is somewhat predictably elicited in situations of powerlessness, an evolutionary approach might explain why, and make sense of the precise psychological symptoms. ‘All things make sense in the light of evolution’ and biopsychosocial approaches are no different. The background model for healthcare, like the background theory for biology, should recognize the importance of evolution.

My paper on ‘specialised minds’ (‘The Specialised Mind’ will be the title of my book, by the way) did a few things. Firstly, it’s an up to date review of the literature on the evolution of individual differences. Most evolutionary theory has considered traits which are either beneficial for the whole species or for a particular sex. Natural selection pushes those traits up in prevalence until essentially everyone of the species/sex shares them. But a critical fact about psychiatric conditions is that we don’t all share them – we are differentially susceptible, both due to genetics and environments. Why should genes that cause these individual differences persist, and why should environmental factors be able to push us into states of depression, rather than simply being limited at, say, moderate sadness? I’m particularly interested in the long lasting conditions; the ‘traits’ rather than ‘states’; ADHD, schizophrenia, autism, bipolar, dyslexia, and so on. My initial hunch was that some kind of adaptive range of variation exists – specialized minds – beneficial to our ancestors, but probably out of place in modern society. During my PhD I’ve also come to appreciate additional theoretical nuances, for instance that such adaptive variation can also have costly extremes (e.g. chronic and debilitating schizophrenia can be a justifiable occasional cost if there are sufficient benefits gained by relatives).

Most evolutionary theory has considered traits which are either beneficial for the whole species or for a particular sex. Natural selection pushes those traits up in prevalence until essentially everyone of the species/sex shares them. But a critical fact about psychiatric conditions is that we don’t all share them – we are differentially susceptible, both due to genetics and environments.

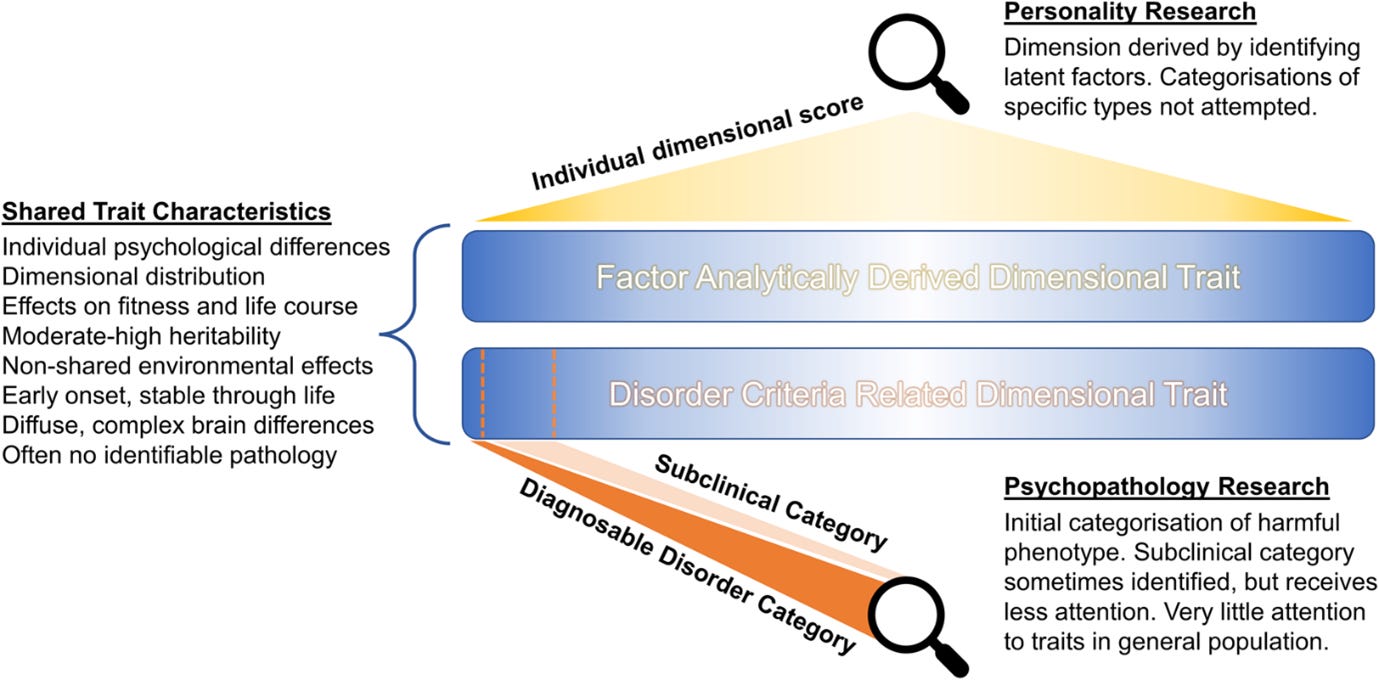

The review takes an approach which I think is critical – linking the theoretical models from evolutionary biology, literature on the evolution of animal and human personality, and relating it to the evolutionary explanations of mental disorders. One important point is that the distinction between personality and psychopathology is one of human decision around how to conduct science and categorise cognition and behaviour, but the division between ‘healthy’ and ‘disordered’ cognition isn’t justified objectively – both personality and psychopathology exist on spectrums, are complexly heritable, show diffuse brain differences, react to nonshared environments, and are early onset, fairly stable, and common. Psychopathology research concentrates on the extremes where dysfunctional lives are evident and diagnoses them as separate entities, whilst personality research cares about scores on dimensions but doesn’t try and distinguish separate types or think about personality extremes (in mainstream academic personality psychology, anyway – specific personality types are commonly trotted out in popular culture). This reflects choices about science, not objective reality. This figure from the paper is relevant:

I also emphasise the core evolutionary forces missing from mainstream discussion on evolutionary psychology and psychiatry – social selection, frequency dependent selection, and social niche specialisation. The basic principle here is that adaptive strategies differ depending on who you are surrounded by and the social environment you are in. At the most basic level, if you are surrounded by cheaters, you shouldn’t cooperate. But this can extend to complex social behaviours, division of labour, and indeed personality differences as individuals fill these so-called ‘social niches’. Everyone knows about sexual and natural selection, but if you want to understand individual behaviours and different adaptive strategies, these forces are crucial! They are massively under-represented in the literature but actually should be ubiquitous amongst social creatures – and humans are a particularly social species. Indeed, the whole of game theory is based on the dynamics of such strategies! Thinking in terms of adaptive strategies (and where they can go wrong – for instance, if they activate in the wrong environment, or are too common, or are forced to a ‘cliff edge’ where the optimum adaptive strategy is liable to go ‘too far’ and become harmful to certain individuals) is essential for understanding individual differences. That’s the main point of the ‘specialised minds’ concept.

The podcast is fantastic by the way and I hear you have a second season coming out shortly? Can you take us through a little bit of the process of how it came to be and running the podcast?

Thanks! Indeed, the ‘Evolving Psychiatry’ second season has already started being released. People can check it out on YouTube or their usual podcast platform.

As I said, when I got interested in evolutionary psychiatry in 2016 I found almost nothing online to sate my interest, which was very surprising (you are also now filling such a niche with this substack!). The EPSIGUK YouTube channel is the closest thing, but it is a bit academic and lengthy, so I thought something at more of an entry level would fill a gap. Then, the CUP Evolutionary Psychiatry book was about to be released and I thought it would be a perfect opportunity to start a podcast series. That provided the first season, and was a bit more rigorous in structure, with one episode on every chapter of the book. This season is more flexible, a bit more conversational, and is hopefully filling gaps that were missing in the last. The plan is to eventually cover every core topic and theory in evolutionary psychiatry in some shape or form, so that a person can begin listening as a complete novice and come out having received a general overview of the field as it stands. But I have a lot on my plate, and prefer working on one or two things at a time rather than juggling several things continuously and scattering my attention, so it will be carried out in seasons rather than as a continuous release.

What are you working on currently? And what's in store for you in the near future?

As I’m finishing up my PhD, I’m working on publishing the work which I’ve been working on continuously over the last eight years – which is all around improving methodology and making evolutionary psychiatry (and indeed psychology) a more precise and scientifically tractable field, with a clear research paradigm and way of formulating and testing hypotheses. The ‘just so storytelling’ critique is problematic for evolutionary psychology – making up some convincing sounding story on the basis of too little evidence – it is all too appealing to conjure up such stories, both in psychology and psychiatry. This is also the major (fair) criticism you hear from other scientists, and with a background in philosophy of science, honestly, I think its often valid. To overcome this, I’ve developed stricter definitions of evolutionary dysfunction, and am working on a better scientific method for interpreting the little evidence we have available to compare and validate hypotheses to the best of our ability – what philosophers sometimes call the ‘inference to the best possible explanation’. A lot of this is quite technical, but I think its an important step if we want evolutionary psychiatry to be taken seriously.

The ‘just so storytelling’ critique is problematic for evolutionary psychology – making up some convincing sounding story on the basis of too little evidence – it is all too appealing to conjure up such stories, both in psychology and psychiatry.

To give a quick overview of the method, it’s trying to address a problem for all evolutionary hypotheses – the most important facts are hidden in the past – we have no time machine to go back and see what a dyslexic or schizophrenic would be doing over the hundreds of thousands of years behind us. However, we can instead use modern evidence and infer something about the evolutionary process. For example, we can discover a genetic component predisposing towards a disorder diagnosis, and analyse that genetic component to see if it’s a new mutation or whether it is common in the population and complexly integrated with the human genome. In most cases for common disorders (but with notable exceptions, particularly cases with intellectual disability), the genes are common, not novel mutations, and they need some evolutionary explanation for their persistence. Similarly, we can assess other circumstantial features of the condition: is it more common in males or females? When does it appear in life? How long does it last? Does it appear under certain environmental circumstances? These form clues we can use as guideposts, also considering the full characteristics of the condition and how we would expect it to manifest and affect our ancestors. The aim of the method is to help put the pieces of the puzzle together in a particular structure of systematic review with formal and theoretically sound analytical principles. When it’s applied, the most successful attempt to make sense of all the available evidence and form a coherent picture should stand out as the leading evolutionary hypothesis – that is, until new evidence is discovered, or a better hypothesis comes along and makes better sense of what we know!

To give a quick overview of the method, it’s trying to address a problem for all evolutionary hypotheses – the most important facts are hidden in the past – we have no time machine to go back and see what a dyslexic or schizophrenic would be doing over the hundreds of thousands of years behind us. However, we can instead use modern evidence and infer something about the evolutionary process.

I’ve also initiated projects with evolutionary anthropologists trying to study mental health in the few remaining small-scale and hunter-gatherer societies, the ‘MAPPING Mental Health’ working group. Watch this space as we try and actually study what mental disorders look like in the least industrialised societies on Earth.

Finally, I’m planning and involved in various projects investigating the psychological effects of evolutionary explanations – during my very first experience glimpsing principles of evolutionary psychiatry, on that night in 2016, one of the most powerful emotional effects was in reconsidering all the people I had been automatically judging as ‘broken’. I’m convinced that explanations matter – the evidence supports this when it comes to comparing biogenetic and stress explanations, and a recent study showed evolutionary explanations reduced self-stigmatisation about depression. Seeing mental health through an evolutionary lens is radically different to the current norm, and I think it will have positive effects, on sufferers, clinicians, teachers, employers, and so on.

I’m convinced that explanations matter – the evidence supports this when it comes to comparing biogenetic and stress explanations, and a recent study showed evolutionary explanations reduced self-stigmatisation about depression.

Evolutionary explanations place the explanation of your mind in the context of our long ancestral history – a very different world – and emphasise that costs often come downstream of a process of adaptation. We are sitting at a very strange point in human history, and your problems can make sense by shining a light on that history. This doesn’t mean they suddenly become easy, but it does often mean you aren’t simply broken. Taking an evolutionary perspective on our own and each other’s mental health problems should, I believe, make us more open to talk about, understand and accept each other. It should prevent parents feeling a sense of grief and despair when their child receives an ADHD or autism diagnosis. It should prevent those diagnosed feeling totally hopeless and disadvantaged, and encourage them to embrace their strengths and face their weaknesses. We all have innate talents and shortcomings. Some of those difficulties warrant a psychiatric diagnosis and can be supported by medical help. But the challenge of facing ourselves and making the best of our biology in a bizarre modern world is universal. Placing these conditions in the framework of our evolutionary story helps us, I believe, tell a better story to ourselves about our own individual lives.

Where do you see evolutionary psychiatry will go in future, what kind of barriers do you foresee?

I’m an optimist by nature, but the history of psychiatric and academic paradigm shifts is one of gradual change over decades, so I think our baseline expectation should be a slow and steady rise in interest, perhaps primarily in the public domain, whilst professionals who have been trained without any hint of evolutionary explanations likely stick to what they were taught.

We should probably look at how evolutionary psychology is integrated into modern psychology as a reference – actually, the number of dedicated ‘evolutionary psychologists’ are dwarfed by the psychologists, sociologists, economists and so on who reference evolutionary psychology casually. I think that’s probably what will happen with evolutionary psychiatry – everyone will sort of know that there are evolutionary explanations for these states and traits, but it probably won’t have thousands of dedicated researchers. Honestly, that’s fine – so long as the core ideas are floating around the public consciousness (which they aren’t yet) then I think we will be on the right track. The barriers are probably mainly going to be human, raised by people who have been trained in non-evolutionary approaches and whose careers and livelihoods rely on society valuing expertise in their own approaches! Incentive structures rule everything…

Then again (as I said, I’m an optimist) I do think we live on the precipice of a very new era. The internet and novel technologies (such as being used in this very post!) are radical and offer possibilities for much faster information transmission and cultural evolution. Thinking about the possibilities such technologies afford is a bit of a side passion of mine – I actually wrote an article on this here. I can certainly see evolutionary approaches spreading more quickly than the usual ‘the progress of science is measured in gravestones’ dynamics. I hope that happens. We shall see.

Adam was also kind enough to feature us on the Evolving Psychiatry podcast - please see links below for our discussions ‘Evolutionary Education and Impact’ with Professor Henry O’Connell and ‘Entering Evolutionary Psychiatry’ with Dr Gurjot Brar:

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast

Are diseases or their conditions inherited? Do these conditions always materialize or only partially? What is the difference between genotype and phenotype? God, life is complicated!