Personality Disorders - Clinical Case Series #10

Adapted/Edited by Dr Gurjot Brar from "Evolution and Psychiatry: Clinical Cases" by Prof. Henry O'Connell

Welcome to the tenth in our clinical case series, exploring common mental disorders through the lens of evolutionary psychiatry. A ‘problem-based learning’ (PBL) approach is taken with learning outcomes defined at the outset, followed by several clinical encounters with fictional scenarios, interspersed with theory responding to the learning objectives. This method has emerged globally in medical curricula and has a good evidence base in medical education promoting self-directed learning. We hope you enjoy this format and look forward to your feedback.

This case series will often refer to key principles defined in the following article published in July 2023 which serves as a primer:

Personality Disorders

Learning Objectives

Outline the key clinical features, epidemiology, aetiology and management strategies utilized in treating people with personality disorders

Outline how an evolutionary perspective can enhance our understanding of personality disorders

Outline how an evolutionary perspective can enhance treatment strategies for people with personality disorders

It’s Bonny & Clyde again…

Dr Jane Kelly is the Liaison Psychiatrist for the City Hospital. She is relatively new to the hospital, having started only a year before and she is building a multidisciplinary team (Clinical Psychologist and Clinical Nurse Specialist) to help deliver a consultation and liaison service to the medical and surgical wards along with the accident and emergency department.

It is a regular weekday afternoon and Dr Kelly is just finishing on the medical ward when she receives a call from her secretary: ‘Dr Kelly we have an urgent, double referral. The accident and emergency doctor said you don’t know the patients but they are well known down there. It’s a couple and they’re known as Bonnie and Clyde’.

Dr Kelly calls to her office and reviews the referral: ‘Dear Psychiatry. Please assess and help us manage this very troublesome pair of patients, Faye Donoghue and William Battles, both aged 24. Multiple and repeat presentations to the hospital in crisis for the past three years. Usually in the context of either or both of them self-harming or being violent with each other. They’re binge drinkers and they also go through phases of cocaine use. They have a child together but he’s in care. They don’t have medical or surgical problems and they are a huge drain on our staff. They can be very threatening. Today the issue seems to be that one of them has taken an overdose of 100 paracetamol tablets but they won’t tell us who took the overdose and neither will agree to having blood tests or any treatment’. Dr Kelly notes that the term ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ was not included in the referral letter.

Dr Kelly arrives in the accident and emergency department and the senior nurse and Consultant approach her immediately. ‘Please help. We can’t cope with this pair any longer. Maybe you can have them both admitted to the psychiatric unit?’

Dr Kelly arranges for a chaperone and attempts to assess the couple, who are seated quietly in a cubicle. ‘I’m Dr Kelly and I’m here to help you if possible. Would you like to talk to me separately or as a couple first?’ There is a long silence and William then turns on Dr Kelly and shouts: ‘How dare you come in and think that you can help us. You know nothing about what we’ve been through. We want to die and you’re not going to stop us’. Faye begins to weep loudly and falls on her knees then falls forwards and starts punching the floor until her fists start to bleed. Dr Kelly leaves to call for help and returns with staff from the emergency department. And Suddenly then they are gone. In an instant, William and Faye have stormed out of the hospital before anyone had the opportunity to detain them.

Dr Kelly returns to the accident and emergency staff. ‘We don’t know what they’ve taken, if anything. And they are off the hospital premises. We could send an Authorised Officer to try and assess them and start an involuntary admission process, but I would advise against that. My initial impression, based on what you’ve told me, their pattern of presentations and how they interacted with me today is that they both have personality disorders. If they present again, call me’.

The senior nurse looks at Dr Kelly: ‘So can you tell us what a personality disorder is and why they can’t be admitted to the psychiatric unit for treatment?’

Learning Objective 1:

Outline the key clinical features, epidemiology, aetiology and management for personality disorders

Personality disorders involve pervasive and lifelong cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns that are largely inflexible and often maladaptive and and that which cause significant functional impairment or subjective distress.

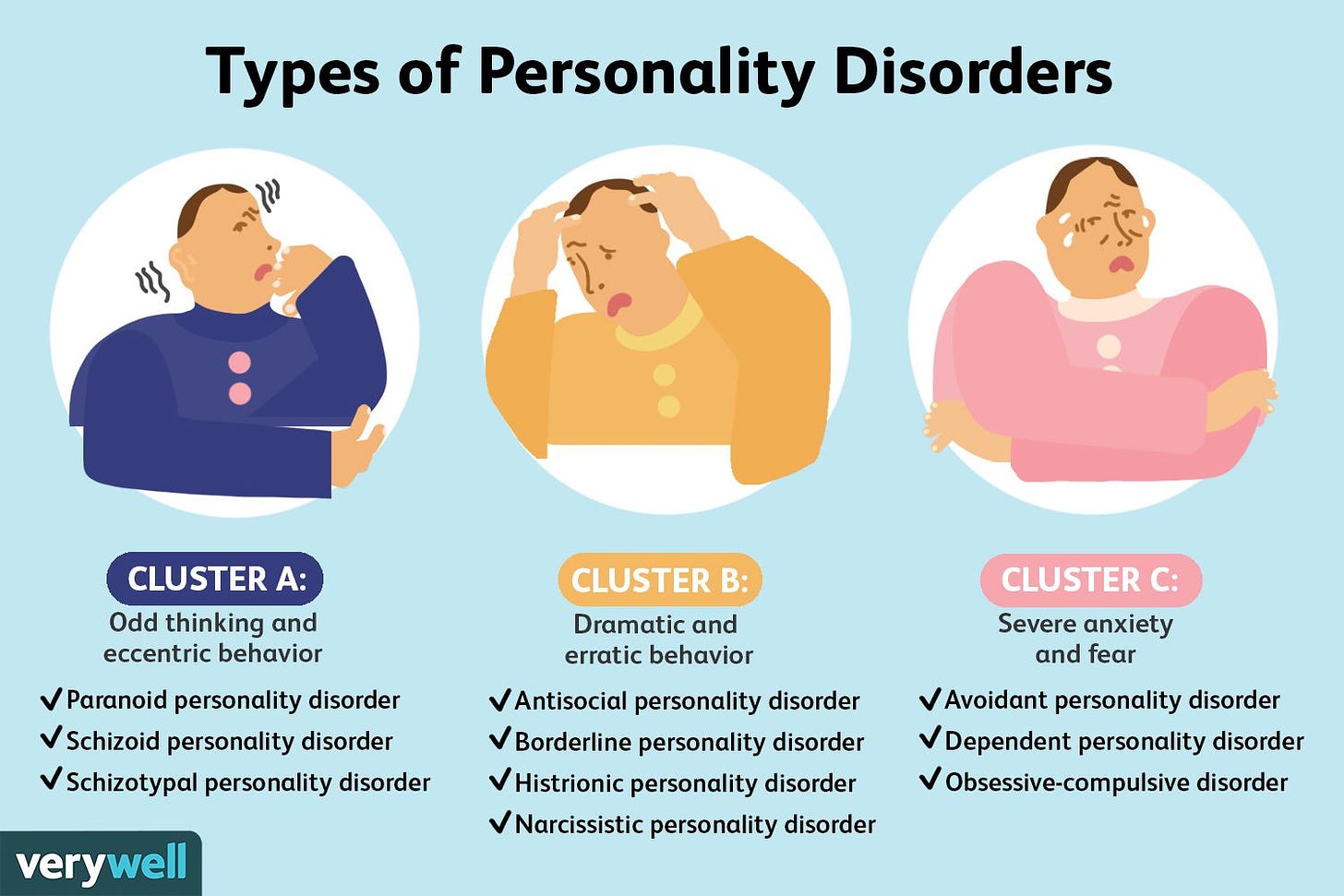

DSM-5 categorizes personality disorders into three broad groupings: Cluster A or ‘eccentric’ (schizoid, schizotypal and paranoid), Cluster B or ‘dramatic’ (antisocial, borderline and histrionic) and Cluster C or ‘anxious’ (avoidant, dependent and obsessive-compulsive). Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is the one of the most prevalent and problematic conditions. It is more common in females and is characterised by features of unstable interpersonal relationships, emotional regulation difficulties, a fear of abandonment, feelings of emptiness, impulsivity and risk taking-behaviours and dysphoria. It is also often accompanied by recurrent self-harm behaviour. Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) on the other hand, is more common in males and highly prevalent (almost 50%) amongst prisoners and offenders (Fazel & Danesh, 2002). It is characterised by a long-term pattern of disregarding others' rights, starting in childhood or adolescence, a tendency to manipulate others, show little empathy or remorse, and struggle with forming stable relationships. The behaviour often leads to criminal activity, as they rarely learn from consequences. (APA, 2013; Fisher et al., 2024).

The clinical features vary widely depending on the type of personality disorder and comorbidity of more than one personality disorder or multiple traits is common. Personality disorders are common in the general population with prevalence rates for any type of personality disorder of 10-20% at around 10-12% and muchand with higher rates again in clinical populations (Volkert et al., 2018; Winsper et al., 2020). For example, BPD has a lifetime prevealence of 6% (Grant et al., 2008) in the general population but is present in 15-28% of psychiatric patients (Gunderson et al., 2018), of 30-50%. Aetiology is multifactorial and may include genetic factors and early life experiences, especially abuse and neglect, although it would be an oversimplification to associate personality disorder with early trauma alone (Bierer et al., 2003).

Personality disorders are common in the general population with prevalence rates for any type of personality disorder of 10-20% at around 10-12% and muchand with higher rates again in clinical populations (Volkert et al., 2018; Winsper et al., 2020). For example, BPD has a lifetime prevealence of 6% (Grant et al., 2008) in the general population but is present in 15-28% of psychiatric patients (Gunderson et al., 2018), of 30-50%.

Treatment is primarily psychotherapeutic in nature with psychotropic medication having a role in treating co-morbid psychiatric disorders and, to a lesser extent, in attenuating traits such as impulsivity and aggression. Dialectical Behavioural Therapy, has evidence for treatment of BPD (May et al., 2016) and mentalization‐based therapy (MBT), transference‐focused psychotherapy (TFP), and schema therapy (ST) have been developed and are empirically supported, but their implementation in routine clinical practice remains patchy (Gunderson et al., 2018; Bateman et al., 2015).

‘I’m afraid they’re back…’

Dr Kelly is back in the accident and emergency department two hours later to assess another patient. Midway through her assessment she hears loud screaming and a nurse comes into her cubicle. ‘It’s your pair, Bonnie and Clyde. They’re back. He says she just ran in front of a car and she’s hurt. He says it’s your fault because you let them leave ’.

William and Faye are subsequently ‘cleared’ medically and surgically and Dr Kelly arranges to see Faye on her own in a cubicle. With careful questioning and lots of time she manages to establish that Faye was sexually abused by an uncle between the ages of 5 and 12. She started to use drugs and alcohol from the age of 14. She met William when she was 16 and gave birth to their son a year later. Since their son was taken into protective care due to concerns about their suitability as parents, Faye and William have lived an increasingly chaotic life. Neither can hold down jobs for long and they spend whatever money they get on alcohol and drugs.

After another hour William has calmed considerably and is open to talking to Dr Kelly. He tells her how his father was a dangerous criminal who was frequently in and out of jail because of various violent offences, including armed robbery on one occasion. William was beaten by his father from an early age and he witnessed his mother being assaulted by him too on countless occasions. William was expelled from school at age 14 for fighting and poor attendance and subsequently lived on the streets for two years until he met Faye. He admits to being ‘rough’ with Faye but: ‘We love each other like no one else can. We would be dead without each other’.

After her assessment, Dr Kelly meets with the accident and emergency staff and outlines a contingency plan for further assessments. The senior nurse looks puzzled: ‘So you’re saying they don’t have a treatable mental illness, Dr Kelly. So why are they so troubled and so impossible to deal with? And why do they keep harming themselves and each other and anyone they can get close to?’ The accident and emergency Consultant then adds: ‘We need some type of crisis management plan to deal with this pair. We’re too busy dealing with real medical emergencies to have time for this type of stuff’.

Learning Objective 2:

Outline how an evolutionary perspective can enhance understanding of personality disorders

Current diagnostic systems describe categorical criteria for personality disorder generally and for specific types, as outlined in the earlier learning objective. These diagnostic systems involve atheoretical descriptions of clinical features and take little account of aetiology. More recently however, in the ICD-11, the categorical system for personality disorders has been replaced with a dimensional approach, resembling the DSM-5 alternative model. Among the DSM-5 personality disorders, only BPD is retained as a distinct and unique disorder, identified through the "borderline pattern specifier (World Health Organization, 2022).

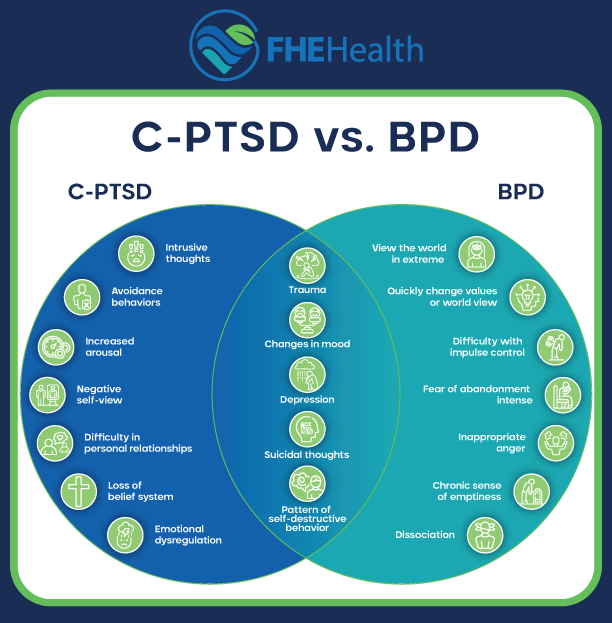

Categorical approaches for personality disorder appear to be changing. For example, there is ongoing debate with differentiating borderline personality disorder from complex-PTSD which was introduced in the ICD-11 (Karatzias et al., 2023) and the large overlap with BPD and its co-morbid disorders may be an artefact of using categorical criteria (Leichsenring et al., 2024).

As with all psychiatric disorders, evolutionary perspectives can be grounded in the seven key principles outlined here in our previous article:

Mismatch: our bodies are unprepared to cope with modern environments.

Infection: bacteria and viruses evolve faster than we do.

Constraints: there are some things that natural selection just can’t do.

Trade-offs: everything in the body has advantages and disadvantages.

Reproduction: natural selection maximizes reproduction, not health.

Defensive responses: responses such as pain and anxiety are useful in the face of threats.

Viewing Diseases as Adaptations (VDAA): For example, major mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder are unlikely to have any benefits for individual sufferers and should not therefore be viewed as adaptations.

When considering individual patients, the SOCIAL review of systems developed by Randolph Nesse (see below) is also a useful outline for facilitating understanding of biopsychosocial goals and associated behaviours and emotions.

In contrast to the categorical system of classification used by conventional diagnostic systems, the evolutionary perspective brings an increased emphasis on aetiological factors and the potentially adaptive aspects of certain behavioural and emotional responses to challenges and threats that, when extreme, constitute maladaptive personality disorders.

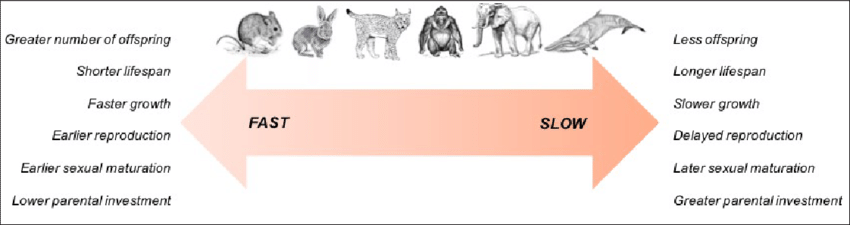

The evolutionary perspective also introduces the concept of fast and slow life history strategies and offers a potential system for conceptualizing personality traits and personality disorders.

Life History Theory offers a lens through which personality disorders can be seen as outcomes of evolutionary adaptations to early environmental pressures. Disorders like Antisocial, Borderline, or Narcissistic Personality Disorder may reflect fast life history strategies adapted for survival in unpredictable, unstable environments, while disorders like Obsessive-Compulsive or Avoidant Personality Disorder may reflect slow strategies focused on long-term planning and control in more predictable environments. Understanding personality disorders through this evolutionary framework helps to explain the trade-offs in behavior that, while adaptive in certain environments, may become maladaptive in modern, complex societies.

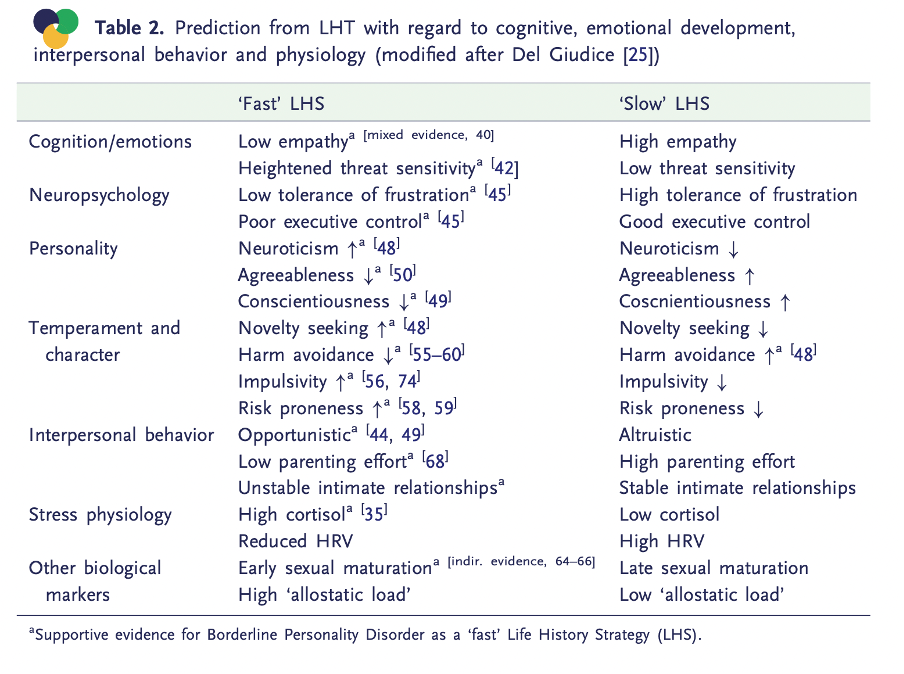

Martin Brune (2016) has outlined how the new DSM-5 dimensional model of personality traits can be used to describe how fast and slow life history strategies relate to cognition, emotional development, interpersonal behaviour and physiology, outlined in the table below:

For example, it is plausible and understandable that individuals who are abused and neglected in childhood are likely to sub-consciously adopt fast life history strategies in order to improve their chances of survival and reproduction, as with Faye Donoghue in this case. Martin Brune (2016) sums this up with the statement that ‘individuals with negative expectations about future resources tend to pursue fast life history strategies’. Neurological correlates supporting this theory include findings of reduced volume in limbic areas and the corpus callosum along with reduced frontal lobe blood flow in individuals with early adversity. In addition, genetic factors are also be important, as with her partner William, who may have inherited an increased risk of antisocial traits in view of his father’s history and profile, not to mention the impact of early exposure to violence and aggression.

‘individuals with negative expectations about future resources tend to pursue fast life history strategies’ - Brune (2016)

While personality disorders generally involve maladaptive traits and patterns of behaviours, the evolutionary perspective outlines how such traits and behaviours may have potentially adaptive and protective effects, at least in milder forms. The evolutionary perspective may thus help destigmatize personality disorders and help healthcare professionals to develop a more nuanced and empathic approach to assessing and supporting people with these conditions. This view does not contend that these disorders are adaptive in themselves but instead that sub-threshold or ‘diluted’ phenotypes, as Brune (2016) puts it, may well constitute successful reproductive strategies, sometimes at the cost of personal wellbeing.

These allow us to answer pertinent questions which current models are unable to; such as the sex differences amongst personality disorders, why aspects of BPD improve with age compared to other psychiatric disorders and why does risk-taking behaviour occur in those with personality disorders? (Brune, 2016).

The evolutionary emphasis on life history strategy and the potentially important role of early trauma, abuse and neglect in many cases on the formation of personality disorders should also help therapists to take a more nuanced and empathic approach when supporting people with personality disorders.

Turning over a new leaf

Two weeks after the accident and emergency department assessments, Dr Kelly is surprised to see that Mia Faye and William show for their outpatient clinic attendance. They both look well, they are polite and cooperative and they seem to be open to engaging with longer term psychiatric support and treatment.

“We’d like to start fresh, turn over a new leaf you know and maybe get to see our son again someday” says Faye. “I want to end this cycle of drinking myself to death and all this drama” adds William.

Dr Kelly is pleased that they are motivated to improve their current circumstances and wonders if they have heard of life history strategies to understand why they are the way the are currently.she starts to think of how evolutionary perspectives may be of use to William and Faye, along with all involved in their care, from the accident and emergency department to the Liaison Psychiatry team.

Learning Objective 3

Outline how an evolutionary perspective can enhance treatment strategies for people with personality disorders

The evolutionary perspective has the potential to help classify personality disorders in novel ways based on fast and slow life history strategies that represent extreme and maladaptive versions of ‘normal’ adaptive responses to adversity and trauma, especially when encountered from childhood.

This novel classification lens is likely to provide a more nuanced and meaningful approach to the study and understanding of personality disorders and bring with it an increased emphasis on aetiology and the ‘understandability’ of how certain behaviours and emotions arise in response to trauma and abuse.

People with personality disorders (as with Faye and William) often pose difficult challenges for psychiatric and emergency services and elicit strong emotional responses from staff. Emphasizing how personality disorders may represent extreme and maladaptive manifestations of normal responses to adversity may help destigmatize these conditions and help therapists and healthcare workers generally to reflect more deeply and connect more empathically with such patients. For example, explaining to Faye that BPD represents a pathological variant of a fast life history strategy (Brune et al., 2010) could explain several of her behaviours and be the first step in helping her and those close to her to accept her personality and to start exploring healthier coping strategies.

Outlining these perspectives directly to patients in the course of psychotherapeutic interactions is also likely to aid self-reflection and improve insight and acceptance into their behaviour. This will work towards identifying and modifying maladaptive emotional and behavioural coping strategies in collaboration with the patient and more appropriately embed adaptive and less harmful coping strategies.

In fact, an evolutionary perspective has the power to enhance existing therapies for psychiatric disorders (Nesse, 2022). Currently only compassion-focused therapy (CFT) has acknowledged evolutionary aspects (Bradley et al., 2007; Gilbert, 2015). The other empirically validated therapies such as DBT and mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) are also likely to be more attractive for patient and therapists and more effective, if an evolutionary explanatory framework is employed (Brune, 2016).

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast

Incredibly insightful and informative. Thank you for putting this piece together!