Schizophrenia & Psychosis - Clinical Case Series #5

Adapted by Prof. Henry O'Connell from "Evolution and Psychiatry: Clinical Cases" - Edited by Dr Gurjot Brar

Welcome to the fifth in our clinical case series, exploring common mental disorders through the lens of evolutionary psychiatry. A ‘problem-based learning’ (PBL) approach is taken with learning outcomes defined at the outset, followed by several clinical encounters with fictional scenarios, interspersed with theory responding to the learning objectives. This method has emerged globally in medical curricula and has a good evidence base in medical education promoting self-directed learning. We hope you enjoy this format and look forward to your feedback.

This case series will often refer to key principles defined in the following article published in July 2023 which serves as a primer:

Evolution – basic principles & applications to health and illness

"Evolution and Psychiatry: Clinical Cases" is available hereThanks for reading Evolution and Psychiatry! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Schizophrenia & Psychosis

Learning Objectives

Outline briefly the key facts about schizophrenia relating to clinical features and diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, aetiology, pathophysiology and management.

Outline the key evolutionary perspectives on schizophrenia/psychosis.

Outline how evolutionary perspectives can help inform individual treatment strategies for schizophrenia/psychosis.

Outline how the evolutionary perspective can help inform research strategies for schizophrenia/psychosis.

“I’m really worried about Rashid”

Dr Mike Mooney is the consultant psychiatrist covering a rural geographical catchment area in the west of Ireland. Dr Mooney’s service is primarily community based with an emphasis on delivering home based care, outpatient clinics and day hospital services. For the more acutely unwell patients, Dr Mooney can arrange admission to the acute psychiatric inpatient unit attached to the general hospital in Ballyduff, the main town in the region. Along with the psychiatric unit, the general hospital also has medical and surgical services. Because the hospital is small, Dr Mooney knows his medical and surgical colleagues very well and has become quite friendly with many of them over the years. One such colleague is the general physician at the hospital, Dr Abdalla Salah. Dr Salah is originally from Sudan and came to Ireland twenty years before with his wife Ruba, also a doctor, so that they could complete their postgraduate training. They chose to remain in Ireland to raise their family and their three children are now young adults.

Late one Sunday night, Dr Mooney receives a call from his friend Dr Salah. ‘Hi Mike. I’m so sorry for the late call. But I need your expertise. I’m really worried about my son Rashid. You know him since childhood and he is nearly twenty-two now. Two years ago, he went back to Khartoum to study medicine and follow in the family tradition. But he struggled from the outset and failed most of his exams. He has been back here with us for the past six months now and he’s going backwards. He seems to lack any motivation, spending most of his time alone in his room. He has no interest in restarting his studies. He doesn’t even look after himself. And Mike, there are times when I think he’s actually quite paranoid. There are no drugs or alcohol involved - I’m pretty sure of that. And it seems like much more than depression or disappointment at how things worked out in medical school in Khartoum. You’re the expert Mike, but it looks to me like he may be may be developing something like schizophrenia. There is a family history – my own uncle had it. Can you call over some day next week to talk to him and see what you think? And can you tell me about this condition – I only know the basics myself’. Dr Mooney gives Dr Salah a brief outline of schizophrenia (see Learning Objective 1) and the features seem to correlate with Dr Salah’s assessment of his son. Dr Mooney agrees to call to the family home and talk to Rashid and his parents early the following week.

LO 1: Outline briefly the key facts about schizophrenia relating to clinical features and diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, aetiology, pathophysiology and management.

Schizophrenia is a major psychiatric disorder characterized by positive (e.g. hallucinations, delusional thinking and formal thought disorder) and negative (e.g. social withdrawal and apathy) symptoms and an often chronic course that is associated with great distress for individual sufferers and their families, along significant loss of function and social capital.

Symptoms should be present for at least 6 months before a diagnosis is made (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), in contrast to the briefer duration but related conditions such as schizophreniform and brief psychotic disorder. There is also substantial overlap in terms of symptoms and genetic risk with conditions such as schizoaffective and delusional disorder.

Traditionally assumed to have a prevalence of 1% across all populations, there now appears to be wide variation in prevalence (McGrath, 2006) from as low as 0.1% to as high as 3% (Kinney et al, 2009). Its high heritability is evident from the concordance of 48% seen in monozygotic twins in comparison to 17% for dizygotic twins (Owen et al, 2007). Drug use, especially potent marijuana from an early age in genetically vulnerable individuals, is also strongly associated with psychosis and schizophrenia (Pearson and Berry, 2019). Further risks factors include, adverse childhood experiences, urbanisation, migrant status, male sex, low socioeconomic status and low subjective social status (Savva et al., 2024).

Treatment is multifaceted and should involve antipsychotic drugs and multi-disciplinary inputs from Occupational Therapy, Social Work and Psychology. Prognosis varies, from once off episodes through to those with chronic relapsing and remitting courses with gradual and sustained social, cognitive and functional decline.

‘This is not the way things were meant to turn out’

Dr Mooney calls to the Salah’s family home to meet with Rashid, as planned. Abdalla greets him warmly: ‘Thank you Mike. It is such a great relief to see you. Please come in.’ Dr Mooney calls to Rashid’s bedroom and knocks on the door. After a long delay, Rashid opens the door and looks out suspiciously. His hair is long, he is unshaven and his clothes look dirty. His room is dark and a stale smell emanates from inside. ‘Dr Mooney. Hello. So, this is a bad sign if they’ve sent for you. I will meet you in the living room downstairs – just give me a moment please’.

Dr Mooney attempts to take a standard history from Rashid. In summary, Rashid has been developing paranoid and persecutory beliefs of increasing intensity over the past two years. He always ‘felt different’ to his two younger siblings and his school friends, but he thought he would ‘grow out of it’. He hoped that by going to Khartoum to study Medicine that he would impress his parents and finally start to ‘fit in’ with the rest of the family. He reluctantly discloses to Dr Mooney how he started to experience psychotic symptoms while studying in Khartoum, primarily third person auditory hallucinations commenting on his actions, and severe paranoia regarding his roommate. He remembers spending several months sleeping with a knife under his pillow as he was convinced that his room-mate was planning to kill him during the night.

He has never disclosed to anyone this level of detail about his symptoms and he has never sought formal medical help or been prescribed medication. ‘I thought Khartoum would sort me out. I thought I would just become a doctor like my mother and father. And now look at me. This is not the way things were meant to turn out’.

‘Why is this condition still around?’

It is now three months since Dr Mooney’s first meeting with Rashid Salah. Soon after that meeting Dr Mooney advised admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit for further observation and commencement of medication and other therapies. Rashid and his family agreed that this was the best course of action. Rashid’s symptoms responded only partially to Haloperidol, Olanzapine and subsequently Risperidone medication. Ultimately, on detailed discussion of the pros and cons with Rashid and his family, Dr Mooney started Clozapine treatment. Rashid had a good response to this medication within days. His positive symptoms of paranoia and auditory hallucinations had already partially resolved with earlier treatment and the Clozapine maintained these improvements along with helping him deal with his negative symptoms such as apathy and withdrawal.

Rashid started to engage with the nursing staff and the Occupational Therapist on the ward. He started to draw and paint and he began to recall how he had enjoyed these activities when he was younger. Towards the end of the admission, Dr Mooney arranged a meeting with Rashid, his parents, his Key Nurse and the Occupational Therapist. Dr Mooney planned to give Rashid and everyone else involved some feedback on his significant progress since admission and to make plans regarding discharge, with a focus on rehabilitation and ongoing recovery. They discussed the background facts relating to schizophrenia and the specific ways in which the condition had been affecting Rashid.

Towards the end of the meeting, Rashid’s father became visibly upset. ‘I am so happy that my boy is feeling better and coming home with us today. But I am also so sad and angry that he has had to put up with this horrible condition. I remember my uncle suffering for years with symptoms, but then he did not have access to medication like Clozapine and specialist therapies. I understand a little about these receptors and the neurochemicals such as Dopamine. But I feel this is only part of the picture. And still I wonder, when we consider the suffering and loss that it causes for every generation, why is this condition still around?’

Dr Mooney gives another broad outline of schizophrenia (see Learning Objective 1). Dr Mooney outlines how schizophrenia does indeed arise relatively frequently in every generation and how there are multiple theories as to why it is such a common feature of the human condition. As many of the theories are speculative and the concepts may be quite technical, it is agreed with Rashid and everyone at the meeting that Dr Mooney will meet separately with his father and go through things with him. Dr Salah will then assimilate the information and provide further feedback to Rashid and the rest of the family (see Learning Objectives 2 and 3).

LO 2: Outline the key evolutionary perspectives on schizophrenia/psychosis

Despite its persistence in every generation and all known ethnicities, schizophrenia is associated with significantly reduced fertility rates (fecundity), leading to the concept of the ‘schizophrenia paradox’ (Liu et al, 2019) and questions regarding its potential evolutionary benefits for the individual and the species. Further compounding the issue, schizophrenia produces heterogeneous clinical pictures (phenotypic variation) (Brune, 2022)

The fact that there are at least nine different evolutionary perspectives on schizophrenia (Brune, 2022; Abed and St John-Smith, 2021) illustrates both the potential strengths and weaknesses of this approach to conceptualising mental illness. Abed and St John-Smith categorize these perspectives broadly into four ‘evolutionary by-product models’ (laterality and language, lipid metabolism, social brain and ‘cliff edge’ fitness) and five other theories relating to potential adaptiveness of the condition, mismatch, sexual selection, a diametric model and life history theory.

A new emerging theory termed the ‘modified aberrant salience hypothesis’ (mASH), based on systems neuroscience, suggests aberrant salience network induction to be key in the development of psychosis (Savva et al., 2024). The ‘salience network’ is a functionally distinct large-scale brain network and dysfunction is associated with psychosis (Mallikarjun et al.,2018; Palaniyappan & Liddle, 2012). This theory is compatible with other evolutionary explanations (such as out-group intolerance) and grounded by evidence in different fields providing consilience.

Additional key theories are summarised below, with the first four relating to ‘evolutionary by-product’ perspectives:

1. The laterality and language model.

The core concept here is that schizophrenia arises due to disrupted brain lateralisation and a failure of hemispheric dominance for language (Crow, 1997).

2. Lipid metabolism hypothesis.

This theory proposes that changes in lipid metabolism perhaps 50,000 years ago led to increased creative capacities in humans, with schizophrenia being a dysfunctional by-product of this process (Horrobin, 2001).

3. The social brain theory of schizophrenia.

This theory proposes that deficits in social cognition (e.g. recognition of facial emotions and interpersonal processes such as reciprocity and trust) are at the core of the condition and arise as a result of aberrant cortical connectivity in fronto-parietal circuits (Burns, 2007; Brune, 2015)

4. The ‘cliff edge’ fitness functions model

In this theory, Randolph Nesse (2019) proposes that our normally highly developed language, social cognition and ‘theory of mind’ capacities overshoot their optimum, thus going over a notional ‘cliff edge’, leading to the extreme dysfunction seen in schizophrenia. There is overlap here between the earlier cited laterality/language and social brain theories along with the sexual selection theory (see point 7 below).

5. Schizophrenia as an adaptation.

An adaptive model of schizophrenia proposes that schizotypal traits in some individuals led to messianic qualities that led to charismatic leadership and facilitated necessary group splitting in our pre-agricultural, hunter gatherer past (Stevens and Price, 2000; Polimeni, 2012).

6. The mismatch model and the out-group intolerance hypothesis

This model proposes that a mismatch between our long and slowly evolved social and cognitive capacities when faced with the very recent and many novel stressors of modern environments leads to conditions such as schizophrenia. The outgroup intolerance hypothesis is implicated in this model (Abed & Abbas 2011, 2014). This model is supported by phenomena such as the higher risk of schizophrenia in migrants and those who have grown up in cities. Furthermore, there are clear distinctions in content of persecutory delusions for males and females. Males report higher rates of persecutory delusions in reference to strange men (possibly due to risks of inter-tribal conflict and death), compared to females who report individuals in their personal environment (possibly due to risks of ostracism and exile).

7. The sexual selection model.

This model proposes that schizotypal traits such as enhanced creativity and superior mentalizing ability are associated with increased fitness through sexual selection, with schizophrenia manifesting in relatives of such schizotypal individuals and representing an extreme, low fitness phenotype (Del Giudice, 2018).

8. The diametrical model of psychosis.

This theory proposes that schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) and autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) involve diametrically opposite phenotypes to each other, with e.g. cerebral overgrowth and reduced social cognition in ASD in contrast to the opposite phenomena in SSD (Crespi and Badcock, 2008).

9. Life history theory.

Life history theory proposes that positive schizotypy (characterized by e.g. unusual beliefs, magical thinking and paranoid thoughts) is associated with enhanced creativity and unrestricted socio-sexuality as part of a fast life history strategy (Del Giudice, 2018). This is in contrast to slow life history strategy associated with negative schizotypy and ASD. This model overlaps with the earlier outlined sexual selection (point 7) and diametrical models (point 8).

LO 3: Outline how the evolutionary perspective can help inform individual treatment strategies for schizophrenia

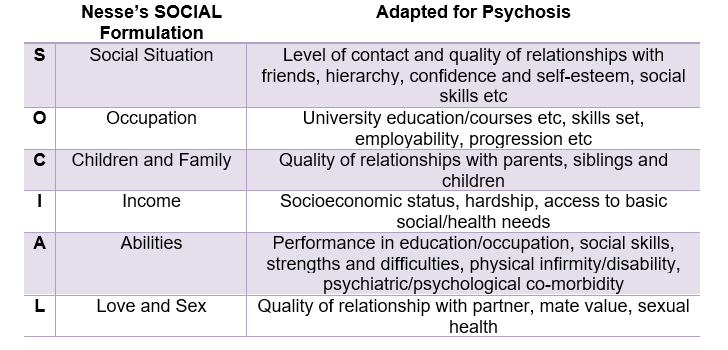

Notwithstanding the multiplicity of evolutionary perspectives on schizophrenia outlined earlier, the direct treatment implications from evolutionary perspectives are limited. However, as with all mental disorders, the SOCIAL review of social systems developed by Nesse (2019), is a useful starting point.

The SOCIAL review of systems takes us beyond the limited ‘biopsychosocial’ approach currently employed in psychiatric assessment and treatment and is summarised below in Table 1. Applying the SOCIAL criteria to Rashid’s current situation thus highlights his many areas of deficit that have arisen because of his illness.

A comprehensive treatment and recovery plan should thus go beyond the mere amelioration of overt psychotic symptoms and involve a multidisciplinary approach in addressing and, if possible, correcting areas of deficiency as identified using the SOCIAL review of systems.

Of the main evolutionary perspectives outlined earlier, the theories relating to the modified aberrant salience network, brain laterality, lipid metabolism and ‘cliff edge’ fitness may have roles in explaining the condition to Rashid and to his family. The power of explanation should never be underestimated in psychiatric treatment and in terms of engaging individuals and families with psychotherapy and what is often a long and slowly progressing treatment journey.

Some aspects of the theory relating to the social brain and schizophrenia could be harnessed in formulating cognitive behavioural therapy approaches to the management of certain symptoms. The mismatch model may have particular explanatory power in this case.

As with other psychiatric conditions when left untreated, the patient may inadvertently adopt harmful ‘fast life history’ strategies. Avoidance of this outcome should be a powerful motivator for early, comprehensive and multidisciplinary treatment.

Finally, considering the impact of environmental mismatch, this focuses our attention on Rashid’s immediate environment. This may produce novel strategies to neutralise harmful aspects of the environment which can be incorporated into the wider treatment plan, e.g. individuals residing in low-same group ethnic densities are predicted to have higher rates of measurable stress and low subjective social status is a risk factor for psychosis (Sapolsky, 2017; Steen et al., 2020).

“Can you put together a research programme on schizophrenia?”

It is now six months after his discharge from hospital and Rashid Salah continues to do well. He continues taking Clozapine treatment and he has been working closely with the Occupational Therapist on developing his art skills and building a portfolio of work so that he could consider applying to Art College. He has decided not to pursue a medical career like his parents. In retrospect, he does not feel that he was ever suited to this career choice and he was only considering it because it was an expectation in his family that he too would become a doctor.

The Salah family invite Dr Mooney and his wife to dinner one evening. Rashid and his sisters have gone to the cinema so it is just the two couples, catching up on old times. Towards the end of the dinner, Dr Salah takes out some papers and spreads them on the table. ‘Mike, you have done a fantastic job with Rashid. We are so happy to see him smiling and enjoying life again. He knows and we know that he will need to continue with the Clozapine. I have learned so much from this experience over the past year or so’. He then smiles and says: ‘To be quite honest, I never really thought that psychiatrists had so much specialist information. I thought we physicians were the brightest of the medical family!’ Everyone laughs as this comment and Dr Salah then goes on.

‘But of course I do see many flaws in how Psychiatry views conditions such as schizophrenia. The field is limited in perspective, just as are many areas of Medicine. And then you explained to me the evolutionary and genetic aspects of schizophrenia and I started to think of the condition in a whole new way. I know a lot of what you told me was theoretical and even speculative, but it helped me accept what was going on for poor Rashid and for the whole family’. Dr Salah now pushes the papers across the table to Dr Mooney. ‘Which brings me to a proposal, Mike. I think we should start a research programme on schizophrenia, but a programme that focuses on novel ways to look at the condition. I think you should take the lead on it and I would be happy to help you in getting support from the hospital research funds. I think we should be going beyond those so called ‘proximate’ questions and start asking questions relating to ultimate causation, i.e. why is schizophrenia still relatively common, does the condition confer any benefits to individuals or families, how are close relatives of people with the condition different to others? Can you put together a research programme on schizophrenia’. Dr Mooney looks at the research grant application forms and looks at Dr Salah and smiles: ‘This is a big project, Abdalla. But I would love to get going on it’. (See Learning Objective 4).

LO 4: Outline how the evolutionary perspective can help inform research strategies for schizophrenia

The range of evolutionary perspectives summarised earlier in Learning Objective 2 above provide a potential framework for a whole range of research programmes.

In designing and delivering such research programmes, the following principles should be applied:

Firstly, as with all medical research, the emphasis should be on clinical outcomes as much as possible. Therefore, any hypotheses and research questions that are devised should have an emphasis on treatment strategies for patients and their families.

Secondly, ‘low hanging fruit’ and potentially answerable questions should be addressed first, moving on to more complex questions of aetiology and treatment later. ‘Unitary’ theories should deserve special attention. For example, the ‘cliff edge fitness’ theory (Nesse, 2019) incorporates aspects of the laterality and language models, the lipid metabolism hypothesis, the social brain theory and the sexual selection hypothesis of schizotypal traits. The modified aberrant salience hypothesis (mASH) is also compatible with many other evolutionary theories and is grounded in phenomenology and systems neuroscience (Savva et al., 2024).

Thirdly, research projects should be designed bearing in mind access (or lack thereof) to research tools ranging from the most basic (i.e. standardised psychiatric and psychometric testing, biophysical measurement) through to the more costly (neuroimaging and genetic testing).

The evolutionary perspective has much to offer in the area of psychiatric genetics generally and in the area of schizophrenia research specifically. Specifically, the evolutionary perspective should help guide psychiatric genetics away from the traditional pursuit of ‘schizophrenia genes’ (which clearly do not exist) to a focus on vulnerabilities within fundamental underlying systems relating to e.g. language and social cognition.

Research in understanding if hunter-gatherer communities report psychosis would also shed light on its evolutionary significance, especially considering the vast majority of schizophrenia has heretofore been conducted in so called WEIRD societies that are not representative of the majority of humanity either currently or in our ancestral past.

Finally, collaboration is essential in modern medical research, in order to pool resources, learning and clinical data. Particularly with other fields for example, evolutionary psychology, biology and anthropology. Therefore, before embarking on a local research plan, relevant international colleagues and research groups should be contacted with a view to developing effective liaisons.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast

Disturbed sleep. Not eating. Stresses imposed by the need to hit someone else’s expectations in life and not his own…

Masking up until the point of nearing the ‘edge’ and partially unmasking, where he is allowed to pursue his own path in life.

Medication initially to stabilise, but don’t ignore the change in environment and being away from the influence and expectations of his parents which put him there.

His parents acceptance that his desire to be an artist is acceptable where his mask hasn’t had to slip in it’s entirety… So he still needs therapy.

‘Therapy’ - the continuous rumination and focus on things which over a prolonged period are viewed through the lens of outmoded practices to crow bar in some kind of convoluted solution.

One bloke has no real understanding of what’s going on with his son, so he calls his mate ‘the hammer’ who over a few months confirms his son’s a nail and uses his experience as the foundation/construction of a hypothesis by a couple of blokes over dinner…

This just smacks of lack of critical thinking.

“The SOCIAL review of systems takes us beyond the limited ‘biopsychosocial’ approach currently employed in psychiatric assessment and treatment…”

I beg to disagree. It is an elaboration with a clever mnemonic of the elements of a biopsychosocial approach that has been in place for decades. It offers nothing groundbreaking.