The Modified Aberrant Salience Hypothesis (MASH) for Psychosis

Edited by Dr Gurjot Brar & Prof. Henry O'Connell

It is a real pleasure to introduce to our readers, Dr Costa Savva and Dr Benjamin Griffin who recently published a paper titled: “Towards a Unified Account of Aberrant Salience in Psychosis: Proximate and Evolutionary Mechanisms”

This fresh take on evolutionary mechanisms in psychosis blends findings in systems neuroscience, phenomenology and evolutionary science to arrive at a unified account of aberrant salience in psychosis. In their paper, the authors argue for the case of this theory and provide examples of how it can be tested. As with much of the literature in the field, the evolutionary perspective discussed is complementary and additive with the benefit of dovetailing with other theories in the field such as Abed’s out-group intolerance hypothesis for schizophrenia (Abed & Abbas, 2011)

Please tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got interested in evolutionary psychiatry

Cos: I’m a core psychiatry trainee in the Wessex deanery, and met my co-author and good friend Ben at medical school. After some years as a junior doctor, I decided to undertake a Psychiatric Research MSc, which I found wholly unfulfilling; something was missing from what I was being taught, despite the confident tone the lecturers often struck. Retrospectively, it is clear to me that courses such as these have an overly-reductive focus on the technicalities of poorly-understood proximate mechanisms, and, without realising it, are hamstrung by their implicit neglect of evolutionary theory within their foundational assumptions. Increasingly, I have embraced the pluralism offered by an evolutionary framework, which I have no doubt in time will dominate the paradigm within which we study the philosophical, nosological and biological underpinnings of psychiatry. In other words, evolutionary psychiatry will allow for the evolution of psychiatry into its next phase.

Ben: I’ve been working as a locum doctor in psychiatry for the last couple of years whilst completing a part-time MA in the philosophy of medicine and psychiatry at King’s College London. I am due to start an academic clinical fellowship in psychiatry at Brighton & Sussex Medical School in August this year, which will constitute my core psychiatry training. On Cos’ (very enthusiastic!) recommendation, reading Nesse’s ‘Good Reason for Bad Feelings’ convinced me of the enormous value of an evolutionary approach to psychiatry. My initial reflection was along the lines of what Thomas Huxley said after reading Darwin’s Origin of Species; ‘How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!’. It seemed such a simple insight, but with vast implications. To give just one brief example, I have long felt a significant limitation of “conventional” psychiatry is that it has no account of normal emotions and their functions. An evolutionary approach gives us the tools to start answering these fundamentally important questions in meaningful ways.

Why did you choose to focus on psychosis, where did the interest/conception for the paper come from?

Ben: I’ve been fascinated by psychosis since my early teens after reading about it in Oliver Sack’s book ‘Hallucinations’: it was one of the main reasons I decided I wanted to go to medical school to train to become a psychiatrist! That interest has never left me. Around the time we were beginning to acquaint ourselves with evolutionary psychiatry, I happened to be reading around Kapur’s Aberrant Salience Hypothesis of psychosis. In a joint discussion with Cos, it occurred to us that salience evaluation could be understood as a trait, which could be thought about with the toolbox of evolutionary psychiatry. This formed the basic idea behind our paper.

Could you take us through what the salience evaluation system is and why/how it has evolved?

Cos: In our paper, we introduce the concept of the salience evaluation system (SES); an evolved domain-specific psychological trait that acts as a selective filter to guide attentional mechanisms onto certain external or internal stimuli. This process is occurring in all of us the entire time we are awake. If we consider that the vast majority of daily sensory input is tagged pre-consciously as “not important”, it follows logically that we have evolved specialised apparatus that allow us to imbue certain stimuli with salience, in order to appropriately motivate goal-oriented behaviour, and respond quickly and appropriately to changes in an environment. This ensures a tight coupling of individual to environment as well as a high precision in decision-making and strategic planning and forecasting. There is also good evidence to suggest that the SES is entrained particularly by social stimuli, which dovetails well with theories suggesting that brain complexity drives, and is in turn driven by, social complexity (Dunbar’s social brain hypothesis).

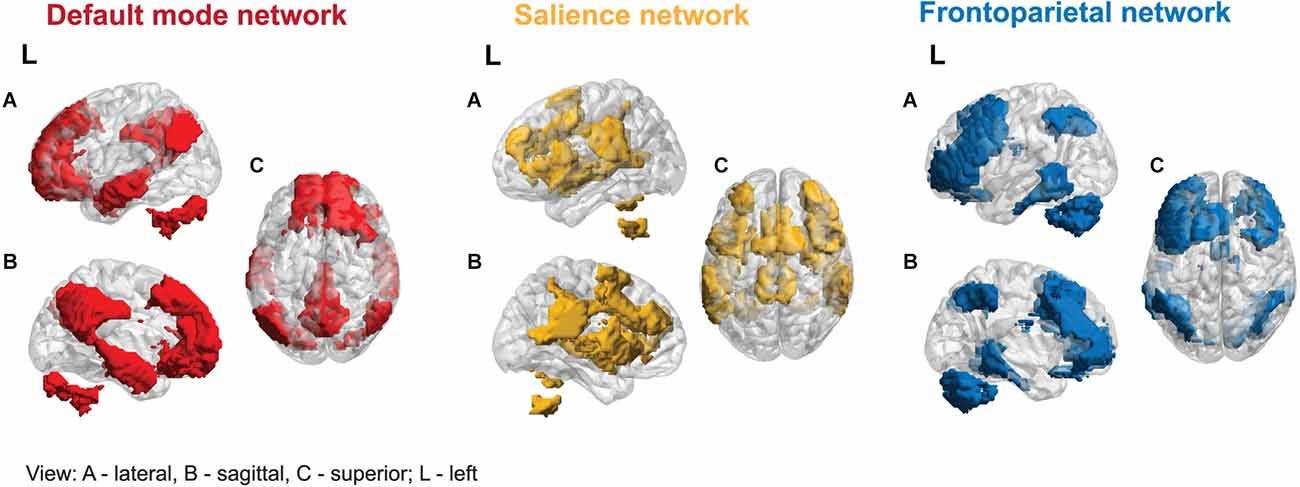

Recent advances in functional neuroimaging have identified distinct, large-scale brain networks, with one of these termed the “salience network” (SN). It is thought that the salience network, anchored in the anterior insular and cingulate cortices, modulates the activity of two other functional networks – the default mode network (DMN), involved in resting-state intrinsic connectivity, and the central executive network (CEN), involved in active higher-order executive decision-making. This is known as the triple-network model and represents an active area of current systems research. It is our contention in our paper that the SN, and associated functional networks, represent good neurobiological candidates for an adaptive SES.

How would this system malfunctioning be relevant to psychosis?

Cos: Referring back to the “selective filter” metaphor, we can think of individuals with acute psychosis as having a malfunctioning filter: the normally adaptive SES becomes conditionally maladaptive in these individuals. If this happens, individuals may falsely impart meaning onto the world around them, which in turn helps entrench delusional beliefs and altered experiences of reality. The trivial becomes pathologically relevant to these individuals, as a result of their salience evaluation machinery becoming impaired. Recent thinking (Kapur, 2003) has reinforced this idea, with subjective experiences of aberrant salience being foregrounded as the central phenomenological characteristic of psychosis.

Essentially, that which is meant to help accurately ascribe relevance and meaning to external or internal stimuli dysfunctions, resulting in disorganised cognition and behaviour. There is emerging evidence, from the field of functional neuroimaging, that dysregulation of the SN can be demonstrated on fMRI in individuals both with, and at high risk for, psychosis. The basic idea here, with reference to the “triple network model” above, is that overactivity of the SN results in overactivity of the CEN, at the expense of the DMN. It’s thought that eventual fronto-cortical atrophy, known to associate with enduring psychotic illnesses, may reflect overactivity-induced excitotoxicity of the CEN.

In broader evolutionary terms, one of the factors that may predispose individuals to a dysregulation of their SES is a mismatched environment to the one we would have originally evolved for (the “environment of evolutionary adaptedness” or EEA). In particular, contemporary industrialised and urbane environments are unique in their overwhelming social complexity. The composition of modern societies is also much more heterogeneous, dynamic and multicultural than it would have been in the EEA. Together, this means that a potentially protective effect of being amongst in-group members may be lost in these environments, and this may explain the well-established increased risk of psychosis seen in migrants living in urban environments: their salience evaluation systems are more susceptible in these mismatched environments to dysregulation.

You’ve discussed how your theory has ‘consilience’. Can you tell us more about how and why?

Ben: Consilience broadly describes the idea that we can be more sure of a hypothesis or theory if two or more independent lines of evidence support it. The theory of evolution gives us a good example of this. Evidence from many distinct areas of study - a non-exhaustive list might include genetics, molecular biology, comparative anatomy and physiology, the fossil record, and the geographical distributions of animals - are all explained by evolution, making the weight of evidence for the theory extremely strong. One of the reasons we were so enamoured with Kapur’s aberrant salience hypothesis is that the neurobiological explanation of psychosis he proposes is consilient with a very different line of evidence coming from first-person experiential accounts of psychosis, termed ‘phenomenological accounts’. We feel this consilience is an important merit of the aberrant salience hypothesis.

Can you tell us about why you believe toxic stress from complex interactions between psychosocial factors has ‘a critical aetiological role’?

Ben: We think looking at epidemiological evidence is very valuable in understanding psychosis. Epidemiology looks at how often diseases occur in different groups of people, and why. Whilst it was once widely believed that there are similar and constant rates of psychosis across different societies and cultures, it has now become clear that there is in fact considerable variation; some studies find 30-fold differences! (Kinney et al., 2009). Epidemiological research therefore allows us to understand which psychosocial factors increase risk for psychosis.

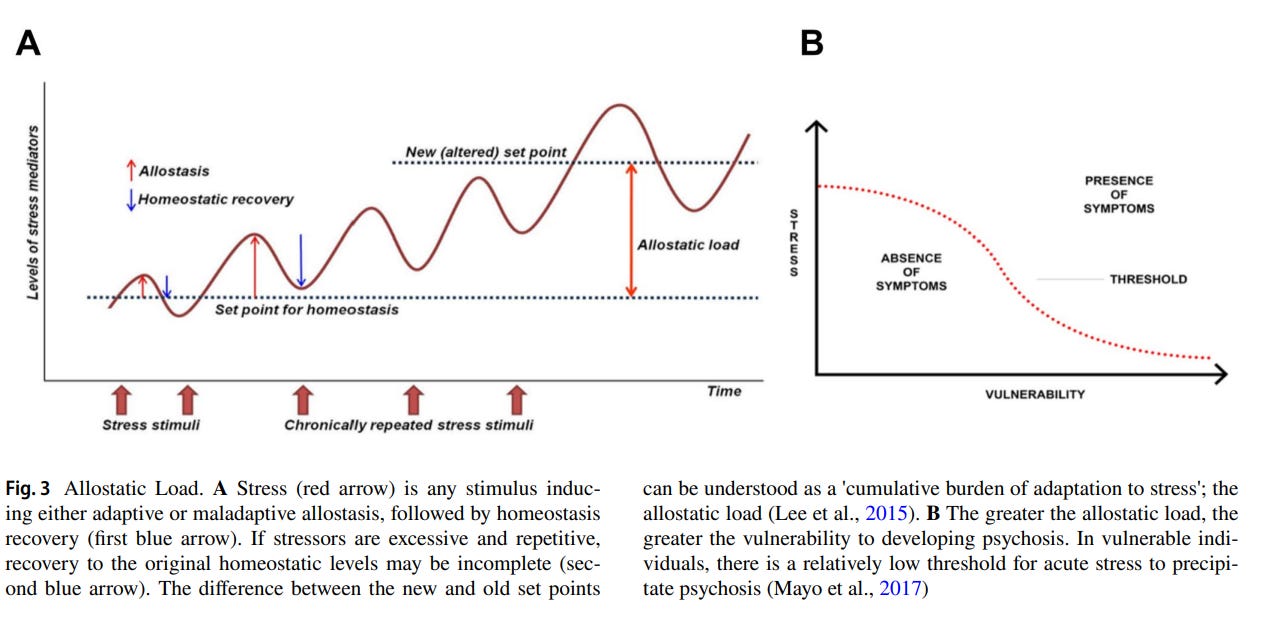

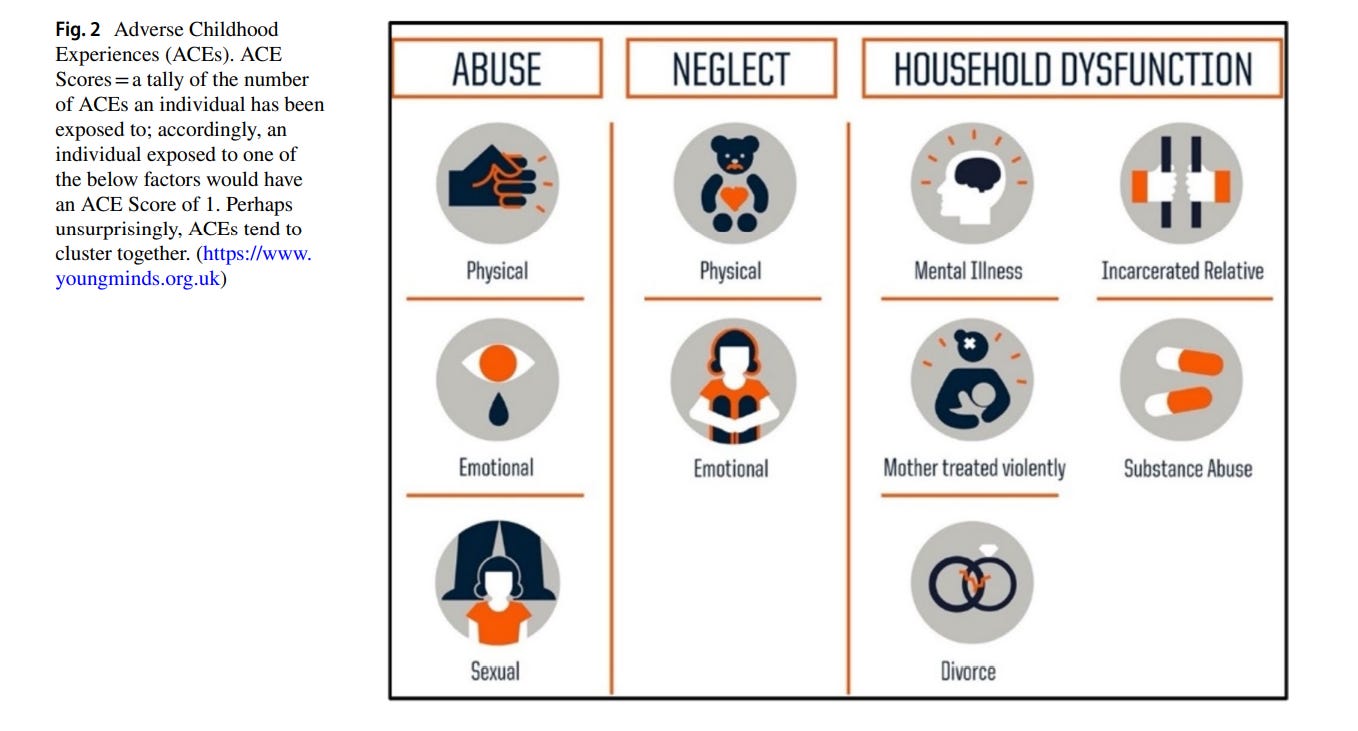

One very important line of epidemiological research for all mental health conditions, including psychosis, is the ‘adverse childhood experiences’ (ACEs) literature. An ACE is defined as ‘highly stressful, and potentially traumatic, events or situations that occur during childhood and/ or adolescence’. A dose response relationship has been shown between ACEs and psychosis risk. In the existing literature what has been termed ‘toxic stress’ has been established as the cause of the deleterious effects on health associated with ACEs (Agorastos et al., 2019). Toxic stress is defined as excessive, prolonged adversity in which the stress system is chronically overactive, disrupting an organism’s normal developmental trajectory and causing long-lasting detrimental health effects. We therefore thought it was highly plausible that other psychosocial stressors which occur during development which have been shown to increase risk of psychosis also cause toxic stress to developing organisms.

The ‘complex interactions’ bit refers to the idea that these risk factors do not operate in causal isolation: research is beginning to show that such things as differences in people’s genes, the timing of the risk factor, if risk factors are happening alongside one another are all important. Consistent with this, there are already emerging lines of evidence that indicate toxic stress alters the neurodevelopmental trajectory, and perturbs the functioning, of the salience network.

How is your modified aberrant salience hypothesis grounded in evolutionary theory?

Cos: We structure our paper in four sections, each dealing with one of Tinbergen’s four questions, with reference to the trait of salience evaluation. We start by considering the proximate mechanism of the trait, namely the activity and inter-connections of the salience network. We then proceed to discuss ontogeny, which is how the SN develops over one’s lifetime, and how risk factors for psychosis (such as urbanicity, migrant status, material deprivation, chronic early life adversity and so on) may interact with one another to alter the developmental trajectory of the SN and predispose to its eventual dysregulation in psychosis. Following these discussions regarding proximate mechanisms, we explore evolutionary questions about the SES such as its adaptive function, its persistence over evolutionary time despite reduced fitness of afflicted individuals, and how psychosis may be increasing in prevalence as a function of mismatch against the EEA humans originally evolved for.

As any good scholar knows, a theory is only sound if it is testable, falsifiable and makes good predictions. Could you take us through some testable predictions based on your theory? Particularly ones that should be a priority?

Ben: We make a number of predictions based upon our hypothesis in our paper. There are two specifically which I find the most interesting. Firstly, given that psychosis is a human species-specific disorder (i.e. does not occur in non-human animals) we make the prediction that the genetic predisposition to psychosis is more likely to be found in recently evolved, human specific areas of the genome. Hence, areas such as the human accelerated regions (HARs) of the genome and non-coding, species-specific genes should have the best chance of uncovering the evolutionary genetic mechanisms for the vulnerability to psychosis. Secondly, although we appreciate this will be difficult to test, given our mismatch-hypothesis we predict that psychosis-spectrum illnesses, as defined in the DSM-5, will not exist in hunter-gatherer populations. Were this to be the case, as our hypothesis suggests, I think this would be a really interesting finding as it flies in the face of the crude genetic determinism which seems to be often evoked in discussions around the aetiology of psychosis.

What are the benefits and implications of adopting the MASH for psychosis?

Cos: The MASH allows us to appreciate that environmental factors play a pivotal (and largely neglected) role in the causation of psychosis, and that cultural variables such as the subjective experiences of racism, economic inequality, ethnic density effects, social status, childhood adversity etc all interact in complex networks to dysregulate the functioning of an evolved neurobiological system. Furthermore, all of these variables can be understood as representing clinically-relevant deviations from the EEA, pointing to the evolutionary mechanism of mismatch.

Whilst this may all sound great, as a largely theoretical piece of work, it is vulnerable to the criticism of being clinically inconsequential. How can we use this information to improve the suffering associated with psychotic illnesses?

a. Implications for future research: Our model encourages further research and quantification of variable interactions to elucidate specific proposals that can form the basis for changing social welfare policy. In line with this, our model suggests that group membership can be protective against psychosis, and that social isolation can perpetuate the disease process. This may allow us to focus on specific social interventions that seek to address some of the evolutionary mismatch. In line with this, our model gives rise to specific testable predictions that can further our understanding of the SES and its link to psychosis.

b. Holistic practice: Our approach allows psychiatrists to provide a more biologically-informed perspective to patients, that engenders as a result a more holistic and compassionate practice. This may help relieve patients (or their immediate family members) of a misperceived responsibility for developing this complex condition, and subsequently may assist in destigmatisation. Simultaneously, this enhances our credibility, legitimacy, and effectiveness as a therapeutic field of academia.

c. Versatility and transferability of methodology: Perhaps more broadly, the methodology we have employed, of seeking to bridge neurobiological, phenomenological, and evolutionary constructs, is generally transferrable to the study of other mental (and physical) illnesses and retains great capacity for a future overhaul of all diagnostic categories. We firmly believe that neglecting evolutionary considerations of psychiatric conditions hampers our ability to fully interrogate the proximate mechanisms. In line with this, we feel that developing theories that can be compatible with evolutionary biology are essential in broadening our rather rigid current conceptions of mental illness.

What are the three main key points that you would like to get across to people reading your paper (or those who do not have the time to read it).

Ben: Firstly, regarding the proximate mechanism of mental illnesses including psychosis: we think that theories should move away from reductive neurotransmitter-based accounts to more systems-based approaches. In our paper we’ve tried to update the neurobiological underpinnings of Kapur’s Aberrant Salience Hypothesis in this way, moving away from the aetiological dopamine hypothesis of psychosis to an emphasis on salience network dysfunction.

Secondly, regarding the ultimate/evolutionary cause of psychosis, in our model the main evolutionary cause of psychosis is a mismatch between aspects of the modern environment and the EEA, which predisposes the trait of salience evaluation to dysfunction in genetically vulnerable individuals.

Finally, we have tried to showcase the value an evolutionary approach can have in deepening our understanding of proximate mechanisms of diseases. We feel that, through applying an evolutionary toolkit to aberrant salience in the case of psychosis, we have been able to develop the hypothesis significantly. The approach we have taken here, expanding a proximate hypothesis of psychosis using Tinbergen’s four questions, could certainly be applied to other disorders.

Thank you both very much for taking the time to talk today, it has been a real pleasure and once again congratulations on the recent publication.

I was wondering if you had any concluding thoughts/remarks, what’s in store for you going forward and how interested readers may follow you and your work?

Cos: Whilst incredible progress has been made in recent decades in the field of evolutionary psychiatry, there remains a long road ahead to develop the ideas further and test them out. What we have hoped to provide in this paper is a very small piece of the puzzle that may stimulate further discussion and ideas. From a personal perspective, I hope to continue working on contributions to evolutionary psychiatry; I’m eyeing up mood disorders as a possible future project! Please feel free to get in touch via email with any questions or thoughts – cos.savva1@gmail.com

Ben: I want to take this opportunity to thank and acknowledge the contribution of our co-author Riadh Abed; without him I am sure Cos and I would not have been able to go from conceiving the idea to getting it published in a reputable journal in the space of about 6 months! For me, working with Riadh and Cos on this paper furthered my appreciation for what can be achieved through collaborating with others. I hope to have the privilege of working with both of them again on future EP projects. I try to avoid all social media, in significant part because I think it exploits various aspects of our evolved psychological mechanisms in potentially harmful ways, so unfortunately I don’t have any accounts to plug for a follow. But I welcome any thoughts via email! I can be reached at benjamin.griffin@kcl.ac.uk.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast