The People's Game: Evolutionary Perspectives on the Behavioural Neuroscience of Football Fandom

A summary of the recently published article, an essay by Dr. Matt Butler, and an insightful interview.

Dear Readers, it is my absolute pleasure to introduce Dr Matt Butler who is a close colleauge of mine. We begin with a summary of his most recent paper titled "The People's Game: Evolutionary Perspectives on the Behavioural Neuroscience of Football Fandom". Now if you’re wondering what football has to do with evolution, mental health and neuroscience, you’re not alone. The summary below is followed by a short essay by Matt explaining himself and his rationale on the topic. Finally I’ve posted a short interview between Matt and I to add a bit more context to this unsual but highly relevant pursuit.

The article explores the deep-rooted human attraction to football (soccer) through an evolutionary lens. The central arguments are that football fandom taps into primal social instincts, such as tribalism and group cohesion, which have been crucial for human survival. It then examines how the communal experience of supporting a football team can trigger specific neurochemical responses, including the release of dopamine and oxytocin, fostering feelings of pleasure and bonding among fans. Additionally, the article discusses the role of mirror neurons in fans' ability to empathize with players, enhancing their emotional engagement with the game. By integrating perspectives from evolutionary biology and neuroscience, the article sheds light on why on earth football holds such a significant place in human culture.

What does evolution have to do with being a football fan?

Recently, two of my divergent interests, – usually kept apart by a metaphorical line of stewards in hi-vis jackets – collided. Outside of being a football nerd, I’m also an actual nerd. I like to think about how people and their brains work, and seem to be paid to do so. One particular research interest I have is in evolution, and how evolutionary processes have shaped human minds and behaviour.

I recently got chatting to a professor of psychiatry, and devoted Liverpool fan, who shares these interests. Why don’t we write a paper on evolutionary perspectives as applied to football fans? he suggested.

A thoroughly good idea.

Not only would writing something like this resemble - without actually being - proper work, football fandom felt like a topic genuinely well-suited to the exploration of evolutionary ideas.

Football is followed globally, and fanatically. This cross-cultural obsession suggests there may be some quite fundamental – and hence evolutionary – aspects to fan behaviour. Taking an evolutionary perspective might help shed light not only ‘how’ football fans behave, but also – a trickier question - ‘why’ we fans do the things we do.

So, firstly, why might sport in general appeal to us upright apes? It might have something to do with the element of competition, and the use of attributes and skills which would have been useful in the evolutionary past (e.g. speed, stamina, dexterity), plus our desire to see compelling (and complete) story arcs. Football may tap into these phenomena more than most sports.

Our gloriously low-scoring game also leads to lots of variability and unpredictability of scorelines. Humans evolved to pay particular interest to things that offer rewards at random and surprising intervals, and football offers that in spades.

We have very evolutionarily old pathways in the brain which use the chemical transmitter dopamine to alert us to ‘reward prediction errors’. This means we get a great feeling when the unexpected happens, and this motivates us to do more of the same to try and repeat the outcome. The world constantly changes, and it made sense for our ancestors to pay attention to novelties, to stumbled upon food sources or places of shelter.

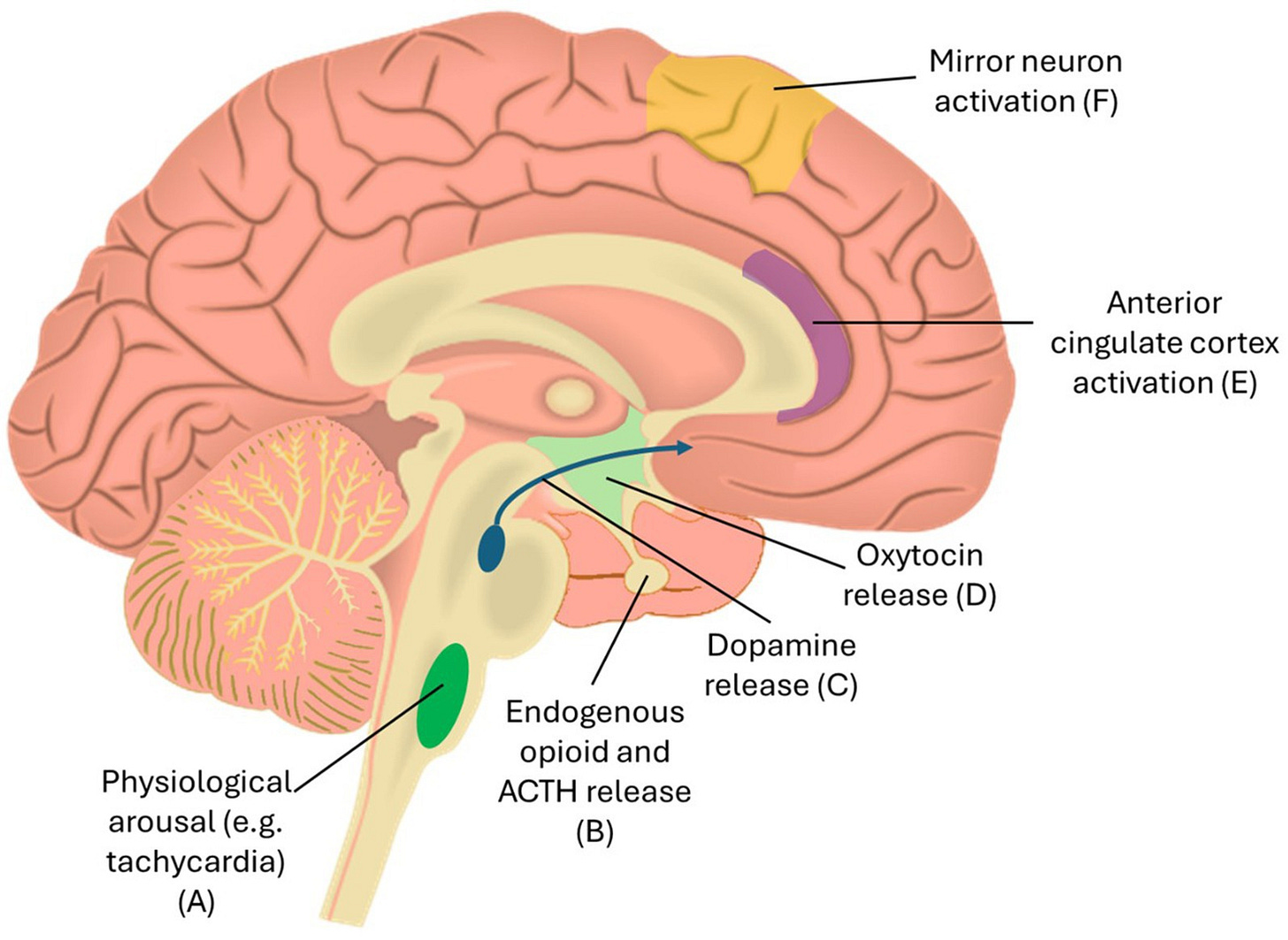

Whenever we attend games, it is a very physical experience. There is good evidence of a whole host of brain and bodily changes occurring in fans watching games, ranging from changes in heart rate and blood pressure (obviously), to the secretion of the stress hormone cortisol, the ‘dominance’ hormone testosterone, and the pro-social hormone oxytocin.

There is also good evidence from brain scan studies of football fans that goals lead to the activation of the limbic system, which is one of the oldest (and deepest) parts of our brains, responsible for emotions and rewards. But the higher-up, evolutionarily newer parts of the brain are also activated by football too. Think of the collective, synchronous movements of crowds, and how everybody nods their head in encouragement as a striker goes to meet a cross. This may be due to mirror neurones: special cells which evolved in apes which facilitate mirroring of behaviour, and hence social learning.

Humans have been undertaking rituals since at least the stone age, but probably further back than this. An archetypal ritual is the rain dance, which of course has no appreciable effect on meteorological systems, but it is useful in the sense that it offers people a feeling of control over an uncontrollable scenario. Rituals thus help resolve uncomfortable feelings of uncertainty in stressful situations. There is good scientific evidence that rituals also facilitate group bonding via the release of endorphins.

Football may be a particularly interesting example of this effect. The collective rituals matchday crowds partake in – the very act of gathering together, the chanting, clapping, booing, cheering, waheeying – does affect the outcome of a game. Indeed, there is good evidence that the home advantage is a real phenomenon, a suggestion supported by the fact that the home advantage disappeared during the crowd-less ‘ghost games’ of the covid-19 pandemic.

In any case, the endorphin saturated experience of the matchday ritual (difficult to remember this during some nil-nil draws) facilitates a process known as ‘identity fusion’, in which a persons’ individual sense of who they are becomes one with the group; in the case of football, the club. This leads, of course, to fans becoming very biased towards their own teams, and makes some people show costly displays of support to ‘prove’ how important the club is.

Strong identification with the group also leads to pleasure at local rivals’ (in evolutionary terms: ‘direct resource competitors’) misfortune. This phenomenon is aptly described by Sigmund Freud’s as the ‘narcissism of small differences’. (I’m not sure if they’ve ever done comparative studies of this effect in goats…)

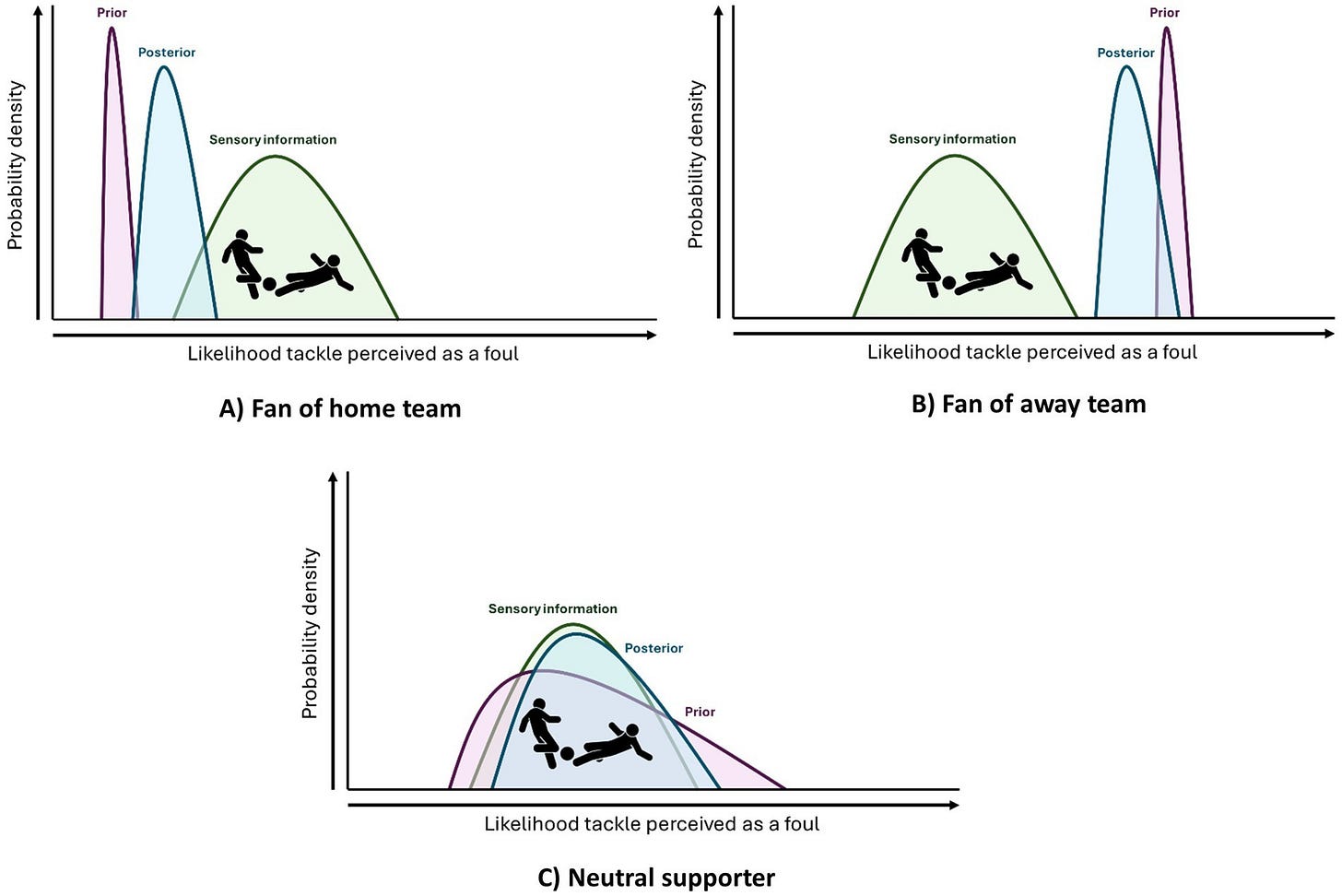

Anyway, more on bias: neuroscience teaches us that our brains don’t simply respond to the world around us, instead they proactively predict what is about to happen, and then subsequently check to see if the predictions are correct. Sometimes, our predictions are held so strongly that they overweigh any competing information.

It is likely in the case of football fans that our brain’s predictions about the superiority of our teams (and hence our very own identities!) are so strong that we literally perceive the same match differently than a rival fan or uninvested person. Proof that our refs are literally as bad as they seem…

As all of us know, investing in a football team has significant effects on emotional well-being. Out constant optimism as fans (‘this season will be different’) and our propensity to look back with fondness on past glories highlights ways in which evolution has equipped us with means to cope with adversity and uncertainty by maintaining a rosy outlook.

Research on football fans has also shown how defeats and losses, far from disuniting people from their club, is just as likely to cause us to double-down on our support. This would have been a particularly important tendency for human tribes in times of resource scarcity in our deep evolutionary past.

Although the science certainly indicates that football takes advantage of many of our evolutionary propensities, it is certainly less clear if football has direct effects on the mental health and well-being of fans. But perhaps we don’t need science to answer this question: the friends we make at the football, the cherished memories of league wins, and the self-sacrificial joy we feel from a last-minute winner at St Elsewhere (a) goes a long way.

Taking evolutionary perspectives on football fandom can help further our understanding of wider human behaviours. Grandiosely, thinking about football fans’ behaviour in this way may also help inform us how lager groups, such as nations and religions, interact with each other, particularly in times of scarcity, hardship, and resource competition.

Who said football wasn’t important?

-Matt

Please introduce yourself for those who don’t know you!

I have been besotted with Chester Football Club since a formative 1-1 draw twenty-five years ago. When not cheering on the Blues, I might be queueing outside the home of football on Wembley Way, playing 5-a-side in Brixton, or watching Peckham Town FC at the Menace Arena.

In rare snatches of free time away from football, I work as a registrar in psychiatry at South London and the Maudsley, and a Wellcome Doctoral Clinical Research Fellow at King’s College London. I have a particular interest in neuropsychiatry.

How were you introduced to the field of evolutionary psychiatry and what interested you in it?

I can’t remember exactly how I was introduced to the field, but I think my first proper engagement with it was writing an essay for the Royal College of Psychiatrists Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group (EPSIG) a few years back. I’d always understood evolution as a truly fundamental law of biological systems, and continued to be baffled at the paradoxical lack of focus on the topic throughout medical training.

I wrote the essay on some speculative (but testable) evolutionary hypotheses about resignation syndrome, a rare but debilitating culture-bound condition which has some similarities with functional coma (also known as dissociative stupor). I was glad to win the higher trainee essay award for it.

Patients with resignation syndrome had been caught amidst political rows about whether their symptoms were imagined or feigned; but as a neuropsychiatrist I knew that mind-body disorders are terrible afflictions which are just as real as the next disease.

There was (and still is) a real lack of understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of resignation syndrome and related disorders, and I thought that evolutionary perspectives could help start us develop an understanding of the causative mechanisms.

What prompted you to write this paper on evolutionary perspectives on the behavioural neuroscience of football fandom?

The idea had been lying dormant as a mind seed for quite a few years, but it was encouraged to germinate recently after a conversation with Prof Henry O’Connell, himself a Liverpool fan from the fields of Anfield Road and a real rose in the evolutionary garden.

As a football fan, I’ve always been equally as fascinated by what happens off the pitch as what happens on it. Football is so enduringly popular – and being a fan feels so deep and primal in many ways – that of course there must be evolutionary principles underpinning fan behaviour and motivation.

A few years back I’d read a book on the topic, The Soccer Tribe, authored in the 1970s by Oxford United FC director - and semi-famous evolutionist - Desmond Morris. He wrote of the powerful social forces which bind football fans together, and the relationship between their behaviours to an evolutionarily informed understanding of Homo sapiens’ tribal history.

It’s a great book, the only that I’m aware of that pairs football and human evolution. But it is also very much of its time, and given the lack of serious discussion on football and evolution in the intervening years, we thought there was a gap in the literature.

Where do you see the place of evolutionary psychiatry in the future and what kind of hurdles do you anticipate?

I am involved on the periphery of the RCPych EPSIG group, and together with some members have been putting together a paper which summarises UK trainees’ perspectives on evolutionary psychiatry.

My feelings in general echo the conclusions of this paper (currently under peer review): that evolutionary perspectives are too fundamental to ignore, that they already have real-world clinical value, but are currently a little light on empirical proofs.

Evolutionary perspectives are too fundamental to ignore…have real-world clinical value but are currently a little light on empirical proofs

In other words, as a researcher, I recognise the field of evolutionary psychiatry has some beautiful theories, but can fall short in terms of supporting evidence. This is probably because the field is complicated, fundamental, and erstwhile-neglected.

We need more of the brightest minds to gravitate towards the field, to navigate the complicated empirical barriers to advancing evolutionary understanding, and to avoid the trap of the (often status-quo reinforcing) ‘just so’ stories which litter evolutionary psychology and psychiatry.

That being said, I think the future is bright for evolutionary psychiatry. Trainees (and more senior clinicians) already use it as a destigmatising way to explain and treat certain disorders. Patients seem to respond well to evolutionary perspectives.

This is perhaps a little less tangible, but I also think evolutionary perspectives have value in that they help (me, at least) feel more connected to people around me, to my human ancestors thousands of years ago, and to the natural environment which begat me and to which I will one day return.

What are you working on currently? And what's in store for you in the near future?

My PhD is on examining responses to psilocybin in functional neurological disorder. This of course is not directly related to evolutionary psychiatry, but is a passion of mine and is a privilege to work on. If you’re interested in this study, you can find out more here.

I have a couple of other evolutionary psychiatry papers in the pipeline, co-authored with some other excellent people interested in the field. (You can keep up to date with those on the links below.)

I love to write (scientific papers, creative non-fiction, and even fiction), and hope to continue doing so. I’m sure evolutionary theory will continue to be an undercurrent which flows through my words. Perhaps one day there will even be a book about football…

If someone would like to follow your work, where can they find you?

I’m off social media these days, because people can’t be trusted to play nicely on there. I have plans to create a site to host links to my written output, but this is currently under development. Until then, if you’re interested, my Google Scholar or King’s College London pages are probably your best bet to follow my work.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast