Why do Humans use Drugs? - Part 1

Dr Gurjot Brar adapts his essay which was presented before the Addictions Faculty of The College of Psychiatrists of Ireland. Edited by Prof. Henry O'Connell.

Our sincerest thanks to Paul St John-Smith and Riadh Abed for their advice, knowledge and expertise not only in the production of this article but for everything they do for the field.

Drug Use and Abuse

A drug may be defined as any chemical substance that causes a biological effect or change in an organism's physiology or psychology. Drugs are different from substances that provide nutrition (although alcohol can be considered as both a food and a drug, and notably caffeine is found in many different types of food).

Determining whether substance use is actually misuse, has required not only biological criteria but also sociocultural value judgements. These definitions vary across societies and remain debatable. In order to answer the question ‘why do humans use drugs?’, our focus will be on psychoactive drugs that are not primarily sources of nutrition and because their effects are potentially harmful to individuals taking them, or indirectly as a consequence of their effect on behaviour cause harm to others.

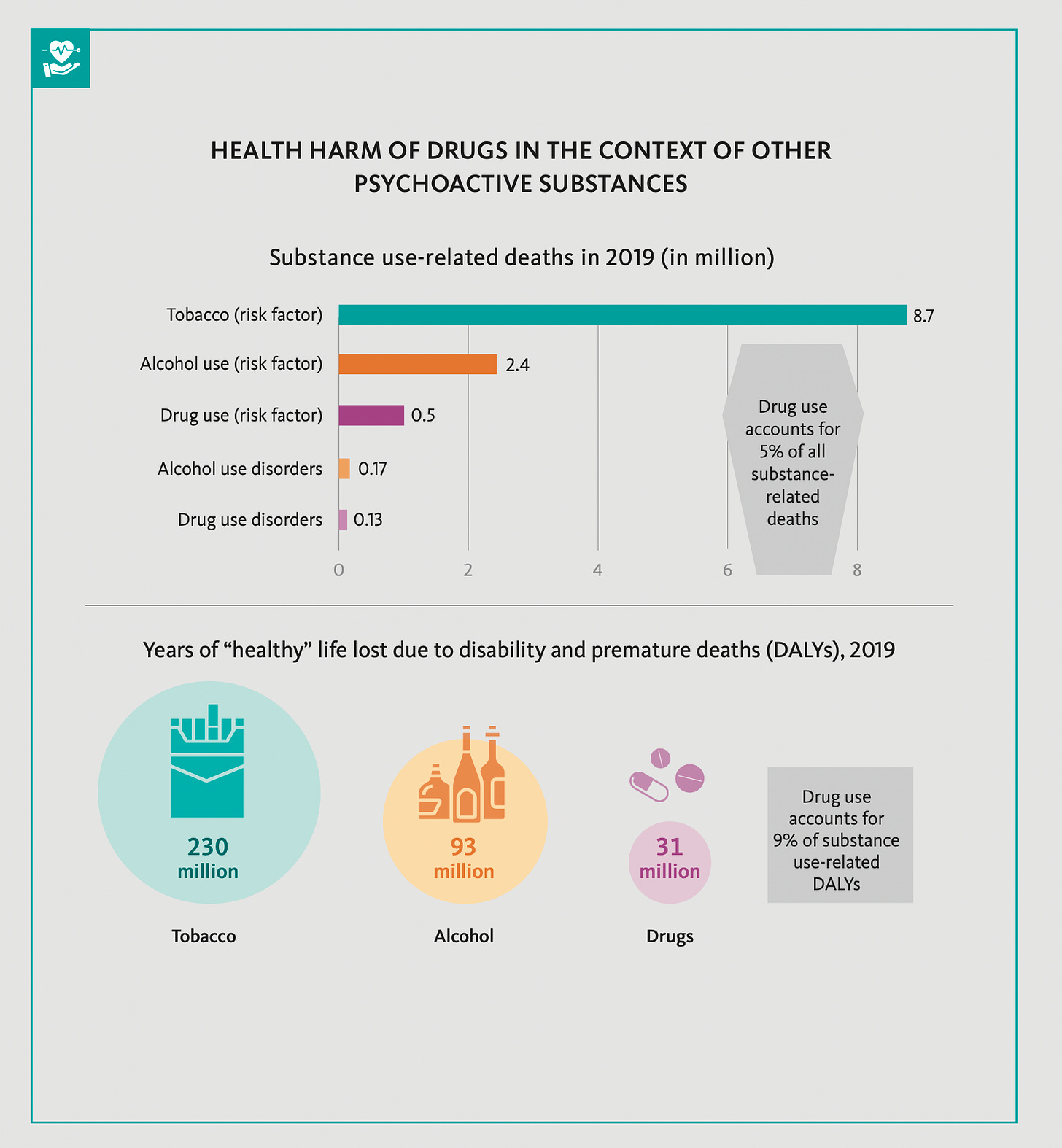

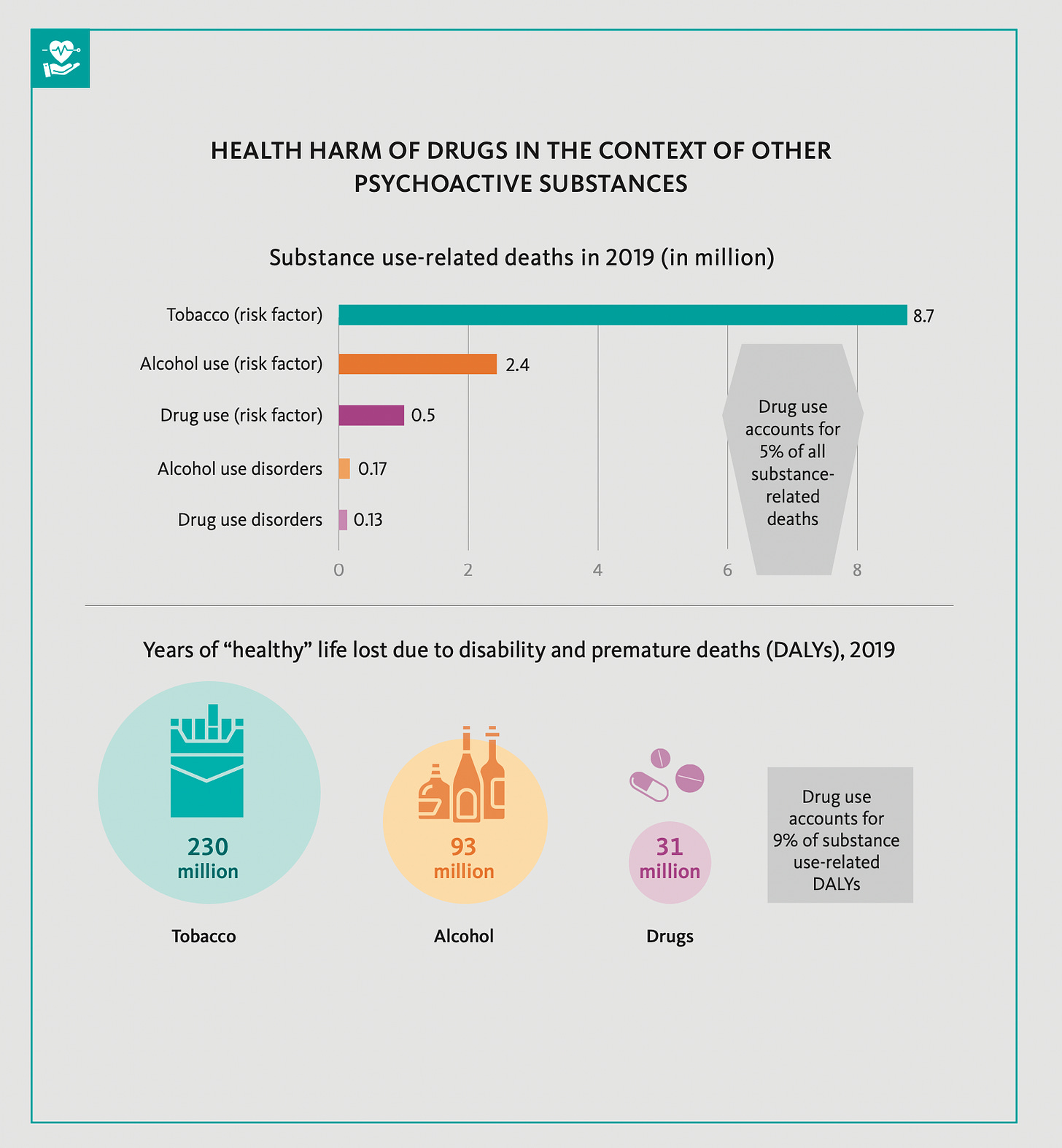

Globally, more than 280 million people aged 15-64 use drugs and/or alcohol, a 26 percent increase over the previous decade. The most frequently used substances include alcohol and nicotine followed by cannabis, amphetamines and ecstasy, then opiates and cocaine (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022). Vulnerability appears to be species-wide and universal with only a minority becoming severely affected.

Substance abuse represents a major public health issue wreaking havoc on socioeconomic structures, and contributes to crime, mental disorder, and medical issues (Roberts et al., 2014). Psychological and psychiatric aspects of misuse include problems related to antisocial behaviour, depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), and diminished abilities to modulate emotions and behaviours in stressful contexts (Haug et al., 2014). Almost half of patients attending community mental health teams (CMHTs) report drug use and/or harmful alcohol use in the past year, and 75-85% of patients attending drug and alcohol services had a psychiatric disorder in the last year (Weaver et al., 2003). Drug use and mental disorders are frequently co-morbid with bi-directional cause and effect, but initiation is at least partially explained by self-medication and/or symptom alleviation (Khantzian, 2003).

It is widely assumed that drug use is initiated by the desire to increase positive affect or reduce negative affect, beginning with voluntary use, typically during adolescence, then multiple factors converging and contributing to its intensification and reinstatement (Berridge, 1997). However, taking an evolutionary perspective reveals a paradox at the heart of this phenomenon. Why are neurotoxins produced by plants to deter consumption by other species specifically sought out and consumed repeatedly by humans? The paradox is further illustrated by the fact that the vast majority of substances used (tobacco, cannabis and betel nut) have non-euphoric effects and their initial use by those neophytes (people who have not previously taken the substance) elicit powerful aversive responses (Sullivan et al, 2008).

To help explore this paradox alongside the universality of drug use in all human societies throughout historical and prehistorical times (St John-Smith & Abed, 2022), it is necessary and illuminating to view this puzzling phenomenon through an evolutionary lens.

The Evolutionary Perspective

We previously explored substance use disorders through a clinical case series lens earlier this year. For those who may be interested in reading the article see the link below:

A Brief History of Substance Use

Evidence of opium use dates back to 3400 BCE, and archaeological data supports consumption of many psychoactive substances in prehistoric times (e.g., cannabis, coca, betel nut, psilocybin mushrooms) (Dobkin de Rios, 1990; Guerra-Doce, 2015). Psychoactive substances have been used and continue to be used in religious ceremonies, by healers for medicinal purposes and by the general population (Hagen & Tushingham, 2019). There is now emerging evidence of plant and fungal toxins used by Neanderthals to previously self-medicate (Weyrich et al., 2017).

The dopamine theory and mechanism of addiction is well established (Nutt et al., 2015). By phylogenetic comparison, dopamine likely was first used as a neurotransmitter over 500 million years ago in the Cambrian Period (Cottrell, 1967). Gradual modification of dopamine pathways have been selected for by processes maximising fitness in different species (Barron et al., 2010). These dopamine reward systems are generally conserved between species and thus allow us to constitute our understanding of the neurobiology of substance use disorders using animal (rodent) models.

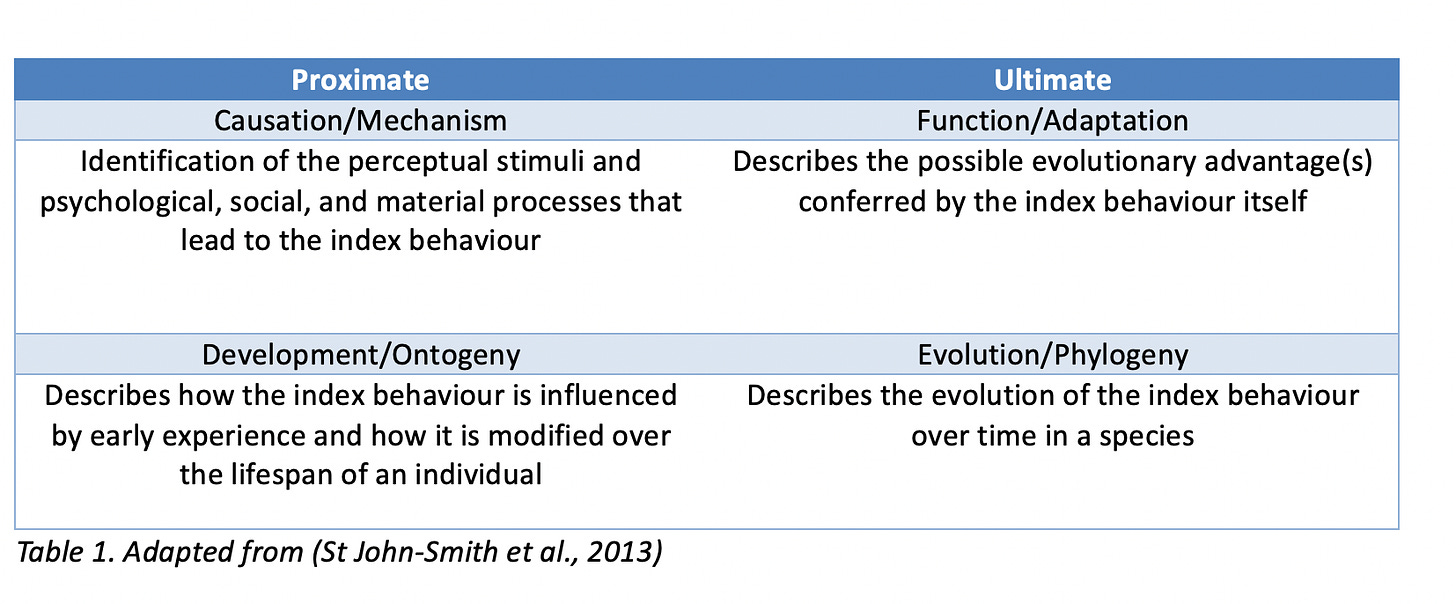

Proximate explanations in psychiatry have focused on mechanisms and ontogeny and these dominate research in addictions. An evolutionary perspective seeks to enhance our current understanding by asking and attempting to answer ‘ultimate’ or ‘why’ questions (See Table 1). These questions include a) Why do plants produce substances that alter the nervous systems of humans? b) Why are some neurotoxin substances addictive to humans? c) Why do humans continue to seek and consume non-nutritional substances and become dependent on them? Thus, evolutionary perspectives allow us to ask questions regarding the adaptive benefits such traits may have conferred in ancestral environments (Abed & St John-Smith, 2022).

Plants that evolved the ability to synthesise alkaloids toxic to predators (e.g., morphine, cannabis, nicotine and cocaine) are likely to have had adaptive advantages in deterring consumption by bacteria, fungi, insects, and animals (Patel et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2008). Those animals that evolved countermeasures against these defences (including enzymatic deactivation, sequestration, and co-consumption of neutralising substances) are likely to have adaptive advantages over competitors, with superior rates of survival and reproduction. Thus a ‘co-evolutionary arms race’ may partly describe why humans have become able to utilise plant alkaloids with their attendant insecticidal and/or anti-helminthic properties (Sullivan et al., 2008).

Evidence of the antiquity of these processes is demonstrated by the variety of Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) which are an important superfamily of enzymes; part of 300,000 distinct CYP proteins which originated from an ancestral gene existing 3 billion years ago (Danielson, 2002). CYPs metabolise various endogenous and xenobiotic substrates (Danielson, 2002) and provide support for exposure to plant toxins in our phylogenetic past (St John-Smith & Abed, 2022). Selection pressures with domestication and agricultural farming of plants lead to the retention of such systems. Examples where local plant ecology is associated with high-frequency polymorphism can be found in Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Here individuals who are ultra-metabolisers have very-high frequencies of 2D6 (Aynacioglu et al., 1999). More famously, Asian populations who are deficient in the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) are prone to alcohol flushing responses (Eng et al., 2007; Harada et al., 1981).

Evolutionary Models of Substance Misuse

Several intriguing questions warrant appreciation of evolutionary explanations. Why are common drugs of abuse (cocaine, opiates, cannabis, and tobacco) plant-derived defensive neurotoxins? (Sullivan et al., 2008). Why do psychoactive substances become substitutes for reality, that alter emotional states in humans that historically signaled increases in Darwinian fitness?

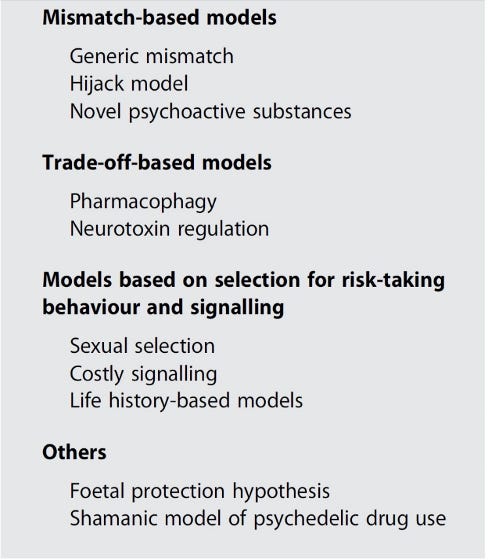

There are a number of evolutionary models of substance misuse which can be summarised under the headings of: Mismatch-based, trade-off-based, models based on selection for risk-taking behaviour or signaling and others (Abed & St John-Smith, 2022; see below):

It is important to note, proposed models and theories can be conceptually similar, overlapping and are not mutually exclusive, perhaps even interacting in unpredictable ways (St John-Smith et al., 2013). As it is often the case, there are many layers of explanations which can complement each other to meet the complexity of the individual.

The Hijack Model

The ’Hijack’ model offers an evolutionary explanation based on the concept of mismatch. According to this model, drugs of abuse have a unique ability to ‘hijack’ the ancient and evolutionarily conserved neural mechanisms in the brain that are associated with positive emotions. These mechanisms evolved over time to incentivise adaptive behaviour, a crucial aspect of human fitness. The mesolimbic dopamine system (MDS) is implicated here to play a key role in Pavlovian condition and other forms of reinforcement learning. Research has demonstrated that although drugs of abuse differ in molecular structures and substrates, they converge on this common pathway where dopamine is frequently implicated. Furthermore, the MDS appears to have evolved to provide reinforcement for natural rewards and behaviours which historically increased fitness (mates, allies, food etc.) (Sullivan et al., 2008). It is important to note that false indications of fitness benefits are problematic. This can occur with increasing positive affect or reducing negative affect in inappropriate circumstances. There is a risk that drug-seeking behaviour increases in frequency displacing adaptive behaviours which confer ‘real’ fitness (Durrant et al., 2009).

Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPSs) and Mismatch

Novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) provide a classic example of mismatch. Chemists can synthesise drug molecules that have never been encountered by humans during their evolutionary history and thus have never evolved defences against them. Psychostimulants such as modafinil and synthetic cocaine substitutes produce false perceptions of fitness and improvement of competitive strategies while sedatives and anxiolytics (benzodiazepines and synthetic opioids) produce euphoria and disinhibition, perceived increased control of fear and enhanced control of painful stimuli (Schifano et al., 2015). As these effects are detached from their evolved, adaptive contexts there are growing concerns how our bodies will manage to defend, detoxify and deal with the unintended harmful effects of such NPSs (Orsolini et al., 2017).

The Pharmacophagy Hypothesis

The pharmacophagy hypothesis suggests ingesting bioactive compounds of plants in small amounts may have been therapeutic over human evolutionary history (Hagen et al., 2013) helping to combat parasites and mosquitos (Sullivan et al., 2008). For example, nicotine is both insecticidal and anti-helminthic, and is associated with reduced helminthic infestation in hunter-gatherer studies (Roulette et al., 2016; Roulette et al., 2014).

Life History Factors

Life history factors explain how those who have experienced adverse childhoods with abusive and unpredictable patterns transpose this view onto the world. Risk-taking behaviour and seeking activities providing immediate gratification can subsume the individual, representing a ‘fast life history’ strategy, one that discounts future consequences. The male preponderance and greater vulnerability of young adults/adolescents to develop alcohol and substance use problems than other age groups can be partly explained by life history theory. Additionally, those unmarried and with a lower socioeconomic status (who may benefit from high risk-taking strategies), have a higher prevalence of substance use disorders (Reyna & Farley, 2006; St John-Smith & Abed, 2022; St John-Smith et al., 2013).

Psychedelics

Psychedelics have been used traditionally for their transcendental and hallucinatory experiences in religious or shamanic contexts and in rituals enhancing group cohesion and bonding (Dunbar, 2022a; Polimeni, 2012). Indigenous sacramental and medicinal therapies have incorporated psychedelics since at least the 4th millennium BC (Nichols, 2016). The modern revolution of psychedelic therapy began in 1938 when Albert Hoffmann isolated Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD). In the following years, psychedelic substances became illegal due to their association with the counterculture and concerns regarding psychosis and addiction (Doblin et al., 2019). The past two decades have seen renewed interest in psychedelics such as psilocybin in the treatment of substance use disorders (Bogenschutz et al., 2022; DiVito & Leger, 2020).

This essay continues with Part 2 exploring the Evolutionary Perspectives on Alcohol Use and Clinical Implications for Treatment and the Future.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to discover more about Evolutionary Psychiatry please consider:

subscribing to our Substack to receive regular content updates

visiting the webpage of the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

visiting the webpage of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring a Youtube playlist on curated presentations by the Evolution and Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

exploring the Youtube page of the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group within the Royal College of Psychiatrists

exploring the Evolving Psychiatry podcast